Rocky Mountain Subalpine Dry-Mesic Spruce-Fir Forest and Woodland

Click link below for details.

General Description

Spruce-fir dry-mesic forest and spruce-fir moist-mesic forest together form the primary matrix system of the subalpine zones of the Cascades and Rocky Mountains from southern British Columbia east into Alberta, south into New Mexico and the Intermountain region. In Colorado these forests are found throughout the mountainous portion of the state at elevations of 2,680 to 3,780 m (8,800-12,400 ft), generally up to the alpine zone, where stunted individual trees form a krummholz dwarf forest. Spruce-fir forest typically dominates the wettest and coolest habitats below treeline. These areas are characterized by long, cold winters, heavy snowpack that may persist until late summer, and short, cool summers where frost is common. Moist-mesic occurrences are typically found in locations with cold-air drainage or ponding, or where snowpacks linger late into the summer, and often grade into subalpine riparian forests. Disturbances include occasional blow-down, insect outbreaks and stand-replacing fire. Stand replacing fires are estimated to occur at intervals of about 300 years for dry-mesic areas, and longer (350-400 years) for more mesic sites. Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) and subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) dominate the canopy, either together or alone. Lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) or quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) stands are common in many occurrences. Common understory species may include heartleaf arnica (Arnica cordifolia), Geyer's sedge (Carex geyeri), fleabane (Erigeron spp.), strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), common juniper (Juniperus communis), silvery lupine (Lupinus argenteus), lousewort (Pedicularis spp.), smallflowered woodrush (Luzula parviflora), little false Solomon's-seal (Maianthemum stellatum), tall fringed bluebells (Mertensia ciliata), Jacob's-ladder (Polemonium pulcherrimum), gooseberry currant (Ribes montigenum), and whortleberry (Vaccinium spp.). Many other forbs may be present, typically with very low cover, and varying according to microsite conditions. Litter and duff typically form a thick layer under mature stands.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Spruce-fir dominated stands occur on all but the most xeric sites above 3,050 m (10,000 ft), and in cool, sheltered valleys at elevations as low as 2,680 m (8,800 ft). The relative dominance of the two canopy tree species and the understory composition vary substantially over a gradient from excessively moist to xeric sites. Spruce-fir forest treeline elevation, species composition, and dominance change with latitude. Subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) increases in importance with increasing latitude, and shares dominance with Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) at tree line over the northern half of the Southern Rocky Mountains ecoregion. In north-central Colorado, "ribbon forest stands of spruce-fir forest occur as islands or long narrow stands of trees in open meadow areas.

Similar Systems

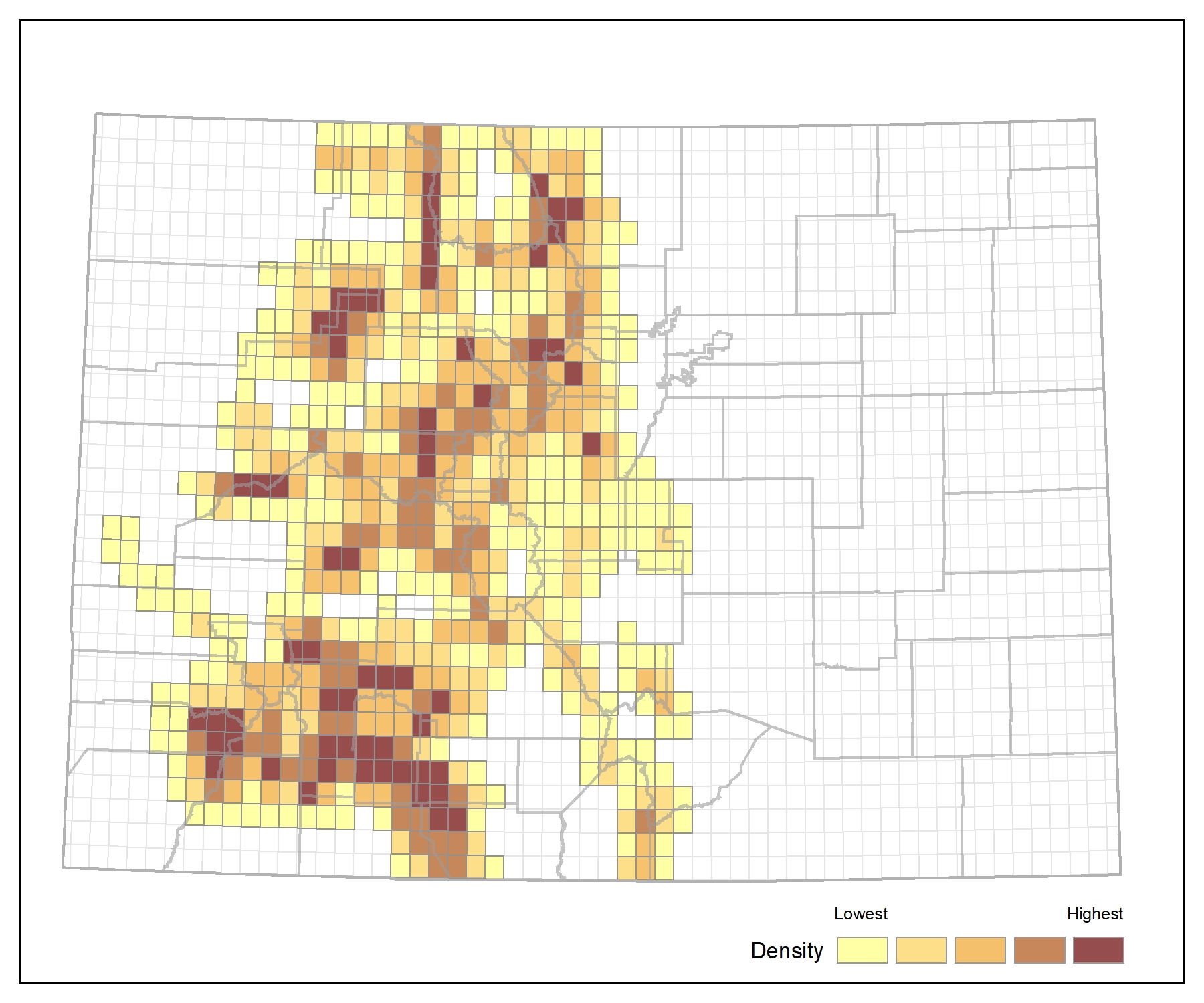

Range

Spruce-fir dry-mesic forest and spruce-fir moist-mesic forest together form the primary matrix system of the subalpine zones of the Cascades and Rocky Mountains from southern British Columbia east into Alberta, south into New Mexico and the Intermountain region. In Colorado these forests are found throughout the mountainous portion of the state at elevations of 2,680 to 3,780 m (8,800-12,400 ft).

Ecological System Distribution

Spatial Pattern

Spruce-fir dry-mesic forest and spruce-fir moist-mesic forest together are matrix-forming; moist-mesic areas may occur as large patches within the dry-mesic matrix.

Environment

These high elevation forests form the matrix of the subalpine zone. Sites are cold, and precipitation is primarily in the form of snow. These forests are found on gentle to very steep mountain slopes, high-elevation ridgetops and upper slopes, high plateaus, basins, alluvial terraces, well-drained benches, and inactive stream terraces. Moist-mesic occurrences are typically found in locations with cold-air drainage or ponding, or where snowpacks linger late into the summer, such as north-facing slopes and high-elevation ravines. The length of the growing season is particularly important for both alpine and subalpine zones, and for the transition zone between alpine vegetation and closed forest (treeline). Treeline-controlling factors operate at different scales, ranging from the microsite to the continental. On a global or continental scale, there is general agreement that temperature is a primary determinant of treeline. At more local scales, soil properties, slope, aspect, topography, and their effect on moisture availability, in combination with disturbances such as avalanche, grazing, fire, pests, disease, and human impacts all contribute to the formation of treeline. Patterns of snow depth and duration, wind, insolation, vegetation cover, and the autecological tolerances of each tree species influence the establishment and survival of individuals within the treeline ecotone.

Vegetation

Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) and subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) dominate the canopy, either together or alone. Lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) or quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) stands are common in many occurrences. Common understory species may include heartleaf arnica (Arnica cordifolia), Geyer's sedge (Carex geyeri), fleabane (Erigeron spp.), strawberry (Fragaria virginiana), common juniper (Juniperus communis), silvery lupine (Lupinus argenteus), lousewort (Pedicularis spp.), smallflowered woodrush (Luzula parviflora), little false Solomon's-seal (Maianthemum stellatum), tall fringed bluebells (Mertensia ciliata), Jacob's-ladder (Polemonium pulcherrimum), gooseberry currant (Ribes montigenum), and whortleberry (Vaccinium spp.). Many other forbs may be present, typically with very low cover, and varying according to microsite conditions. Litter and duff typically form a thick layer under mature stands.

- CEGL000294 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Acer glabrum Forest

- CEGL000300 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Calamagrostis canadensis Swamp Forest

- CEGL000304 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Carex geyeri Forest

- CEGL000919 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Juniperus communis Woodland

- CEGL000321 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Moss Forest

- CEGL000373 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Polemonium pulcherrimum Forest

- CEGL000331 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Ribes (montigenum, lacustre, inerme) Forest

- CEGL000986 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Salix (brachycarpa, glauca) Krummholz

- CEGL000340 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Vaccinium cespitosum Forest

- CEGL000343 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Vaccinium myrtillus Forest

- CEGL000344 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii / Vaccinium scoparium Forest

- CEGL000985 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii Krummholz

- CEGL000328 Abies lasiocarpa - Picea engelmannii Ribbon Forest

- CEGL000305 Abies lasiocarpa / Carex rossii Forest

- CEGL000310 Abies lasiocarpa / Erigeron eximius Forest

- CEGL000325 Abies lasiocarpa / Pedicularis racemosa Forest

- CEGL000332 Abies lasiocarpa / Rubus parviflorus Forest

- CEGL000364 Picea engelmannii / Erigeron eximius Forest

- CEGL000366 Picea engelmannii / Geum rossii Forest

- CEGL000368 Picea engelmannii / Hypnum revolutum Forest

- CEGL000371 Picea engelmannii / Moss Forest

- CEGL000374 Picea engelmannii / Ribes montigenum Forest

- CEGL000377 Picea engelmannii / Trifolium dasyphyllum Forest

- CEGL000379 Picea engelmannii / Vaccinium myrtillus Forest

- CEGL000381 Picea engelmannii / Vaccinium scoparium Forest

- CEGL000527 Populus tremuloides - Abies lasiocarpa / Juniperus communis Forest

Associated Animal Species

Mammals of these high elevation forests include elk (Cervus elaphus), lynx (Lynx canadensis), pine marten (Martes americana), ermine (Mustela erminea), snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus), American pika (Ochotona princeps), Yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris), pine squirrel (also called chickaree Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) and various small rodents. Boreal toad (Anaxyrus boreas boreas) and western terrestrial garter snake (Thamnophis elegans) may be found in this habitat. Bird species include Boreal Owl (Aegolius funereus), Ruby-crowned Kinglet (Regulus calendula), Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus), Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli), Yellow-rumped Warbler (Setophaga coronata), Pine Siskin (Spinus pinus), Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis), Pine Grosbeak (Pinicola enucleator), Canada Jay (often called Gray Jay in Colorado, Perisoreus canadensis), Red-Breasted Nuthatch (Sitta canadensis), Dusky grouse (Dendragapus obscurus), and American Three-toed Woodpecker (Picoides dorsalis). In treeline krummholz stands White-crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys), Mountain Bluebird (Sialia currucoides), Clark's Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana) are often observed.

Dynamic Processes

Engelmann spruce trees can be very long-lived, reaching 500 years of age. This species can rapidly recolonize and dominate burned or cleared sites, or can succeed other species such as lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) or quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). Seedling establishment and survival are greatly affected by the balance of snow accumulation and snowmelt. Soil moisture, largely provided by snowmelt, is crucial for seed germination and survival. Although snowpack insulates seedlings and shields small trees from wind desiccation, its persistence shortens the growing season and can reduce recruitment.

Fire, spruce-beetle outbreaks, avalanches, and windthrow all play an important role in shaping the dynamics of spruce-fir forests. Old-growth in spruce-fir forests is characterized by treefall and windthrow gaps in the canopy, with large downed logs, rotting woody material, tree seedling establishment on logs or on mineral soils unearthed in root balls, and snags. Fires in the subalpine forest are typically stand replacing, resulting in the extensive exposure of mineral soil and initiating the development of new forests. Stand replacing fires are estimated to occur at intervals of about 300 years for dry-mesic areas, and longer (350-400 years) for more mesic sites. Fire return intervals, intensity, and extent depend on a variety of local environmental factors. Fire is much less important in krummholz communities. Spruce beetle (Dendroctonus rufipennis) outbreaks may be as significant as fire in the development of spruce-fir forests. Blowdowns involving multiple treefalls add to the mosaic of spruce-fir stands. Under a natural disturbance regime, subalpine forests were probably characterized by a mosaic of stands in various stages of recovery from disturbance, with old-growth just one part of the larger forest mosaic. This mosaic was constantly changing and highly variable from place to place, so the extent of presettlement old-growth forest is uncertain.

Management

Spruce-fir forest landscapes in Colorado are generally in very good condition, well protected, and minimally impacted by anthropogenic disturbance. Areas of severe beetle-kill may experience increased disturbance from salvage logging or hazard tree cutting. Because natural fire return intervals in these habitats are long, fire suppression has not had widespread effects on the condition of spruce-fir habitat. At a landscape scale, however, age structures of spruce-fir forest are probably somewhat altered from pre-settlement conditions. Spruce-fir forests are subject to disturbance by recreational use, hunting, livestock grazing, mining, and logging, but in general, threats from housing, roads, and recreational development and similar anthropogenic disturbance are minor for spruce-fir habitats.

Climate change projections indicate an increase in droughts and faster snowmelt, which could increase forest fire frequency and extent, as well as insect outbreaks within this ecosystem. It is not known if spruce-fir forests will be able to regenerate under such conditions, especially in lower elevation stands, and there is a potential for a reduction or conversion to other forest types, depending on local site conditions. The vulnerability of these forests to warmer temperatures, drought, and increased mortality from insect outbreaks are primary factors contributing to vulnerability. The restriction of this habitat to higher elevations and its relatively narrow biophysical envelope, slow-growth, and position near the southern end of its distribution in Colorado are additional factors. However, there may be a lag time before the effects of changing climate are evident.

References

- Alexander, Robert. 1987. Ecology, Silviculture and management of the Engelmann Spruce-subalpine fir type in the Central and southern Rocky mountains. USDA FOREST SERVICE. Agriculture handbook no. 659.

- Crane, M. F. 1982. Fire ecology of Rocky Mountain Region forest habitat types. USDA Forest Service final report. 272 pp.

- Donnegan, J.A. and A.J. Rebertus. 1999. Rates and mechanisms of subalpine forest succession along an environmental gradient. Ecology 80:1370-1384.

- Elliott, G.P. 2012. Extrinsic regime shifts drive abrupt changes in regeneration dynamics at upper treeline in the Rocky Mountains, USA. Ecology 93:1614-1625.

- Holtmeier, F-K. and G. Broll. 2005. Sensitivity and response of northern hemisphere altitudinal and polar treelines to environmental change at landscape and local levels. Global Ecology and Biogeography 14:395-410.

- Körner, C. 2012. Alpine treelines: functional ecology of the global high elevation tree limits. Springer, Basel, Switzerland.

- Peet, R.K. 1978. Latitudinal variation in southern Rocky Mountain forests. Journal of Biogeography 5:275-289.

- Peet, R. K. 1981. Forest vegetation of the Colorado Front Range: composition and dynamics. Vegetatio 45:3-75.

- Romme, W.H. and D.H. Knight. 1981. Fire frequency and subalpine forest succession along a topographic gradient in Wyoming. Ecology 62:319-326.

- Schaupp W.C. Jr., M. Frank, and S. Johnson. 1999. Evaluation of the spruce beetle in 1998 within the Routt Divide blowdown of October 1997, on the Hahns Peak and Bears Ears Ranger Districts, Routt National Forest, Colorado. Biological Evaluation R2-99-08. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Renewable Resources, Lakewood, Colorado.

- Veblen, T.T. 1986. Age and size structure of subalpine forests in the Colorado Front Range. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 113:225-240.

- Veblen, T.T., K.S. Hadley, M.S. Reid, and A.J. Rebertus. 1991. The response of subalpine forests to spruce beetle outbreak in Colorado. Ecology 72:213-231