Southern Rocky Mountain Dry-Mesic Montane Mixed Conifer Forest and Woodland

Click link below for details.

General Description

These are mixed montane conifer forests of the Rocky Mountains, found throughout the southern Rockies, extending north and west into Utah, Nevada, Wyoming and Idaho. In Colorado dry-mesic and mesic mixed-conifer forests form a matrix together that can occur on all aspects at elevations generally from 1,830 to around 3,050 m (6,000 to 10,000 ft), where they are often adjacent to ponderosa, aspen or spruce-fir forest. Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and white fir (Abies concolor) are the most common dominant trees, but many different conifer species may be present, and stands may be intermixed with other forest types dominated by ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) or quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). Douglas-fir stands are characteristic of drier sites, often with ponderosa pine and Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii). More mesic stands are found in cool ravines and on north-facing slopes, and are likely to be dominated by white fir with blue spruce (Picea pungens) or quaking aspen stands. Natural fire processes in this system are highly variable in both return interval and severity. Fire in cool, moist stands is infrequent, and the understory may be quite diverse. In addition to the dominant trees, these mixed-species forests may also include Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), and limber pine (Pinus flexilis), which reaches the southern limit of its distribution in the San Juan mountains. Typical understory shrub species include Rocky Mountain maple (Acer glabrum), Saskatoon serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia), kinnikinnick (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), rockspirea (Holodiscus dumosus), fivepetal cliffbush (Jamesia americana), common juniper (Juniperus communis), creeping barberry (Mahonia repens), Oregon boxleaf (Paxistima myrsinites), mountain ninebark (Physocarpus monogynus), mountain snowberry (Symphoricarpos oreophilus), thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), and whortleberry (Vaccinium myrtillus). Where soil moisture is favorable, the herbaceous layer may be quite diverse.

Diagnostic Characteristics

The dry-mesic and mesic mixed conifer types are highly variable in composition, depending on the local conditions. Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and white fir (Abies concolor) are the most common dominant trees, but many different conifer species may be present, and stands may be intermixed with other forest types dominated by ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) or quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). White fir dominates forests at cooler sites. Douglas-fir stands are characteristic of drier sites, often with ponderosa pine and Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii). More mesic stands are found in cool ravines and on north-facing slopes, and are likely to be dominated by white fir with blue spruce (Picea pungens) or quaking aspen stands.

Similar Systems

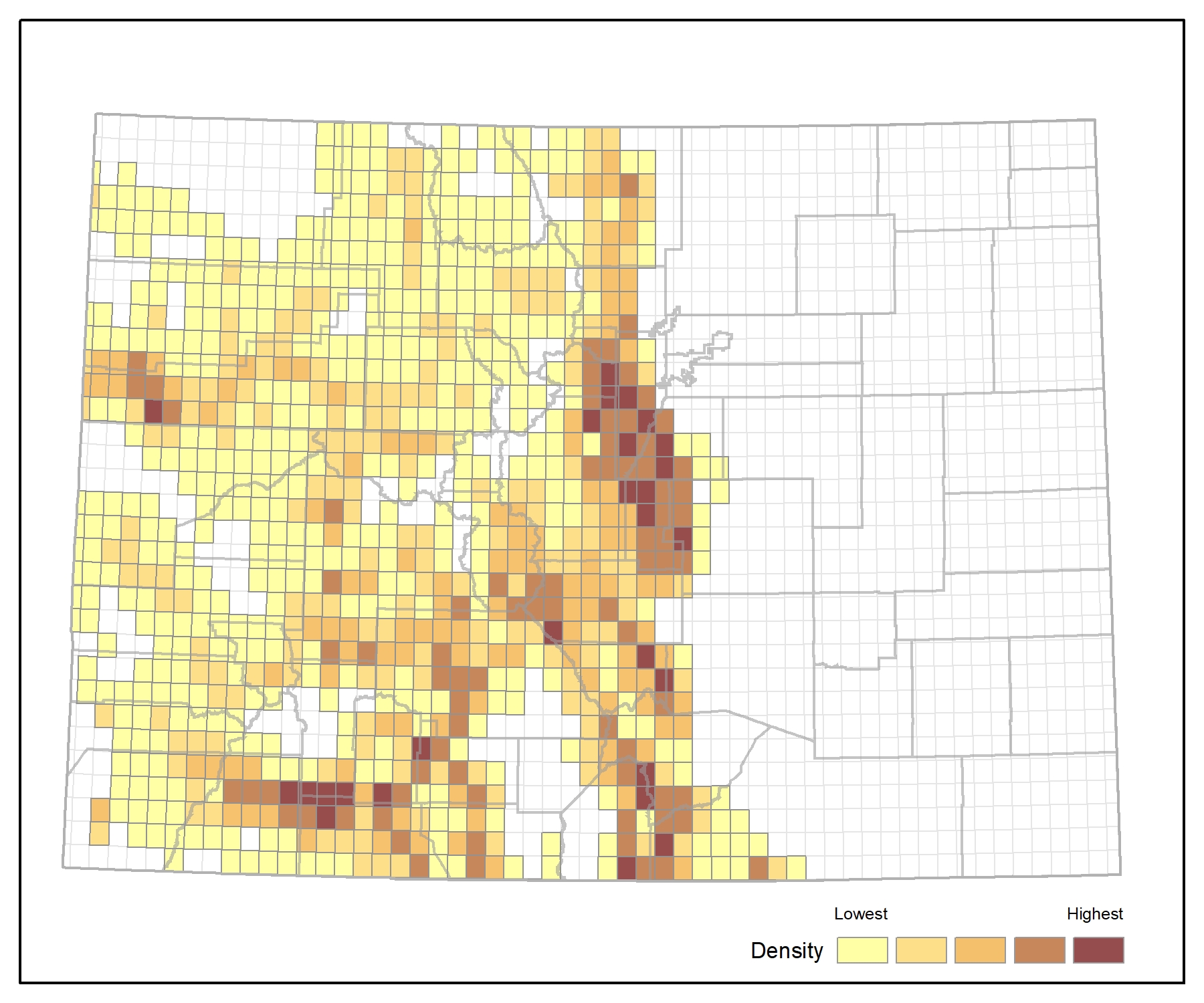

Range

These forests and woodlands occur throughout the southern Rockies of Colorado and New Mexico and on the margins of the Colorado Plateau, extending north to Wyoming and west into Utah, Arizona, Nevada, and Idaho. In Colorado dry-mesic and mesic mixed-conifer forests form a matrix together that can occur on all aspects at elevations generally from 1,830 to around 3,050 m (6,000 to 10,000 ft), where they are often adjacent to ponderosa, aspen or spruce-fir forest.

Ecological System Distribution

Spatial Pattern

These mixed conifer forests and woodlands are generally large patch types, but may occasionally be matrix forming.

Environment

The similar environmental tolerances of mixed-conifer and aspen forest means that the two habitat types are somewhat intermixed in many areas. These forests appear to represent a biophysical space where a number of different overstory species can become established and grow together. Local conditions, biogeographic history, and competitive interactions over many decades are prime determinants of stand composition.

Although cool moist mixed-conifer forests are generally warmer and drier than spruce-fir forests, these stands are often in relatively cool-moist environments where fires were historically infrequent with mixed severity. When stands are severely burned, aspen often resprouts. Warm-dry mixed conifer forests had a historic fire-regime that was more frequent, with mixed severity. In areas with high severity burns, aspen or Gambel oak resprouts and dominates the site for a relatively long period of time.

Vegetation

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and white fir (Abies concolor) are the most common dominant trees, but many different conifer species may be present, and stands may be intermixed with other forest types dominated by ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) or quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides).

Typical understory shrub species include Rocky Mountain maple (Acer glabrum), Saskatoon serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia), kinnikinnick (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), rockspirea (Holodiscus dumosus), fivepetal cliffbush (Jamesia americana), common juniper (Juniperus communis), creeping barberry (Mahonia repens), Oregon boxleaf (Paxistima myrsinites), mountain ninebark (Physocarpus monogynus), mountain snowberry (Symphoricarpos oreophilus), thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), and whortleberry (Vaccinium myrtillus). With higher soil moisture, herbaceous layer diversity increases. Typical graminoids include fringed brome (Bromus ciliatus), Geyer's sedge (Carex geyeri), Ross' sedge (C. rossii), dryspike sedge (C. siccata), Parry's oatgrass (Danthonia parryi), squirreltail (Elymus elymoides), blue wildrye (Elymus glaucus), slender wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus), fescue (Festuca spp.), prairie Junegrass (Koeleria macrantha), smallflowered woodrush (Luzula parviflora), mountain muhly (Muhlenbergia montana), muttongrass (Poa fendleriana), and Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda). Understory forbs include yarrow (Achillea millefolium), heartleaf arnica (Arnica cordifolia), Fendler's meadow-rue (Thalictrum fendleri), mountain goldenbanner (Thermopsis montana), hookedspur violet (Viola adunca), and species of many other genera, including beardtongue (Penstemon), lupine (Lupinus), vetch (Vicia), sandwort (Arenaria), and bedstraw (Galium).

- CEGL000890 Abies concolor - (Pseudotsuga menziesii) / Jamesia americana - Holodiscus dumosus Scree Woodland

- CEGL000255 Abies concolor - Picea pungens - Populus angustifolia / Acer glabrum Forest

- CEGL000240 Abies concolor - Pseudotsuga menziesii / Acer glabrum Forest

- CEGL000431 Abies concolor - Pseudotsuga menziesii / Carex rossii Forest

- CEGL000247 Abies concolor - Pseudotsuga menziesii / Erigeron eximius Forest

- CEGL000265 Abies concolor - Pseudotsuga menziesii / Vaccinium myrtillus Forest

- CEGL000243 Abies concolor / Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Forest

- CEGL000887 Abies concolor / Festuca arizonica Woodland

- CEGL000251 Abies concolor / Mahonia repens Forest

- CEGL000261 Abies concolor / Quercus gambelii Forest

- CEGL000263 Abies concolor / Symphoricarpos oreophilus Forest

- CEGL002167 Ceanothus velutinus Shrubland

- CEGL000894 Picea pungens / Alnus incana Riparian Woodland

- CEGL000385 Picea pungens / Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Forest

- CEGL000386 Picea pungens / Arnica cordifolia Forest

- CEGL002637 Picea pungens / Betula occidentalis Riparian Woodland

- CEGL000387 Picea pungens / Carex siccata Forest

- CEGL000388 Picea pungens / Cornus sericea Riparian Woodland

- CEGL000389 Picea pungens / Equisetum arvense Riparian Woodland

- CEGL000390 Picea pungens / Erigeron eximius Forest

- CEGL000895 Picea pungens / Festuca arizonica Woodland

- CEGL000392 Picea pungens / Juniperus communis Forest

- CEGL000393 Picea pungens / Linnaea borealis Forest

- CEGL000394 Picea pungens / Lonicera involucrata Forest

- CEGL000395 Picea pungens / Mahonia repens Forest

- CEGL000418 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Acer glabrum Forest

- CEGL002754 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Acer negundo Riparian Woodland

- CEGL000420 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Amelanchier alnifolia Forest

- CEGL000424 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Forest

- CEGL002808 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Artemisia tridentata (ssp. vaseyana, ssp. wyomingensis) Woodland

- CEGL002639 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Betula occidentalis Riparian Woodland

- CEGL000428 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Bromus ciliatus Forest

- CEGL000430 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Carex geyeri Forest

- CEGL000897 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Cercocarpus ledifolius Woodland

- CEGL000898 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Cercocarpus montanus Woodland

- CEGL000899 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Cornus sericea Riparian Woodland

- CEGL000433 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Festuca arizonica Forest

- CEGL000902 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Holodiscus dumosus Scree Woodland

- CEGL000438 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Jamesia americana Forest

- CEGL000439 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Juniperus communis Forest

- CEGL000904 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Leucopoa kingii Woodland

- CEGL000442 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Mahonia repens Forest

- CEGL000443 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Muhlenbergia montana Forest

- CEGL000446 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Paxistima myrsinites Forest

- CEGL000449 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Physocarpus monogynus Forest

- CEGL002809 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Poa fendleriana Woodland

- CEGL000908 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Pseudoroegneria spicata Woodland

- CEGL000452 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Quercus gambelii Forest

- CEGL000462 Pseudotsuga menziesii / Symphoricarpos oreophilus Forest

- CEGL000911 Pseudotsuga menziesii Scree Woodland

Associated Animal Species

Characteristic bird species in mixed conifer forest include Steller's Jay (Cyanocitta stelleri), Red-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta canadensis), Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli), Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus), Western Tanager (Piranga ludoviciana), Pine Siskin (Spinus pinus), Townsend's Solitaire (Myadestes townsendi), Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus), Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi), Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis), Clark's Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana), and Northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis). These forests also provide seasonal habitat for elk (Cervus elaphus), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), bobcat (Felis rufus), and mountain lion (Felis concolor), and are home to a variety of smaller mammals including porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum), chipmunks (Neotamias spp.), Abert's squirrel (Sciurus aberti), golden-mantled ground squirrel (Callospermophilus lateralis), pine squirrel (also called chickaree Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus), and bushy-tailed woodrat (Neotoma cinerea).

Dynamic Processes

Long-term ecological dynamics of mixed conifer forests are relatively understudied. There has been considerable recent debate about historic range of variation for stand density and high-severity fire incidence in mixed conifer forests. Natural fire processes in this system are probably highly variable in both return interval and severity, depending on stand composition, site conditions, biogeographic history, and short- and long-term climate patterns. For instance, drought and high temperatures prior to fire initiation are associated with larger burned area as fine fuels become dry. Additional disturbances in mixed conifer forests may be due to wind storms or insect-pathogen outbreaks. Spruce budworm infestations are a major source of tree mortality and can affect landscape-scale dynamics in mixed conifer forest.

Although cool moist mixed-conifer forests are generally warmer and drier than spruce-fir forests, these stands are often in relatively cool-moist environments where fires were historically infrequent with mixed severity. When stands are severely burned, aspen often resprouts. Warm-dry mixed conifer forests had a historic fire-regime that was more frequent, with mixed severity. In areas with high severity burns, aspen or Gambel oak often resprouts and dominates the site for a relatively long period of time. In some locations, much of these forests have been logged or burned during European settlement, and present-day occurrences are second-growth forests dating from fire, logging, or other occurrence-replacing disturbances.

The ecotonal nature of mixed conifer stands increases the difficulty of interpreting their vulnerability to climate change, and their capacity to move into new areas. Changing climate conditions are likely to alter the relative dominance of overstory species, overall species composition and relative cover, especially through the action of fire, insect outbreak, and drought. The diversity of species within this type, however, is expected to increase its flexibility in the face of climate change. Outcomes for particular stands are likely to depend on current composition and location. Drought and disturbance tolerant species will be favored over drought vulnerable species. Species such as blue spruce that are infrequent and have a narrow bioclimatic envelope are likely to decline or move up in elevation. Abundant species that have a wide bioclimatic envelope such as Gambel oak and aspen are likely to increase. Current stands of warm, dry mixed conifer below 2,590 m (8,500 ft) may be at higher risk or may convert to pure ponderosa pine stands as future precipitation scenarios favor rain rather than snow. Upward migration into new areas may be possible.

Management

Mixed conifer forest landscapes in Colorado are generally in very good condition and not severely impacted by fire suppression. In areas adjacent to development, mixed conifer stands may be part of the wildland-urban interface, where they are most likely to be threatened by the effects of fire suppression. Exurban development and recreational area development are a threat to these forests along the Front Range and I-70 corridor in mountain areas. Roads and utility corridors are a source of disturbance and fragmentation in mixed conifer forest statewide, but these stands naturally occur in smaller patches than some other forest types, so threats are minor. A number of tree species in mixed conifer are suitable for timber harvest, so logging is an ongoing source of disturbance in these forests. Threats from livestock grazing and hunting or recreational activities are minimal for mixed conifer forests. Mining and mine tailings are a small source of disturbance.

Stands in the southern part of Colorado have been impacted by the western spruce budworm and drought. Budworm outbreaks are part of a natural cycle in mixed conifer forest, but may be intensified by increasing drought frequency and the generally higher temperatures projected in coming decades. The ecotonal nature of mixed conifer stands increases the difficulty of interpreting their vulnerability to climate change, and their capacity to move into new areas. The diversity of species within mixed conifer forest may increase its flexibility in the face of climate change. Changing climate conditions are likely to alter the relative dominance of overstory species, overall species composition and relative cover, primarily through the action of fire, insect outbreak, and drought. Drought and disturbance tolerant species will be favored over drought vulnerable species. Warmer and drier conditions can be expected to change the relative tree species abundance in mixed conifer forests. Although some stands may convert to other types, the diverse species composition of these forests increases the likelihood that some species will benefit under future conditions. Novel mixed conifer types may appear.

References

- Anderson, R.S., R.B. Jass, J.L. Toney, C.D. Allen, L.M. Cisneros-Dozal, M. Hess, J. Heikoop, J. Fessenden. 2008. Development of the mixed conifer forest in northern New Mexico and its relationship to Holocene environmental change. Quaternary Research 69:263-275.

- Chappell, C., R. Crawford, J. Kagan, and P. J. Doran. 1997. A vegetation, land use, and habitat classification system for the terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems of Oregon and Washington. Unpublished report prepared for Wildlife habitat and species associations within Oregon and Washington landscapes: Building a common understanding for management. Prepared by Washington and Oregon Natural Heritage Programs, Olympia WA, and Portland, OR.

- Crane, M. F. 1982. Fire ecology of Rocky Mountain Region forest habitat types. USDA Forest Service final report. 272 pp.

- DeVelice, R. L., J. A. Ludwig, W. H. Moir, and F. Ronco, Jr. 1986. A classification of forest habitat types of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. General Technical Report RM-131. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Mauk, R. L. and J. A. Henderson. 1984. Coniferous forest habitat types of northern Utah. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report INT-170. Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Ogden, Utah. 89 pp.

- Muldavin, E. H., R. L. DeVelice, and F. Ronco, Jr. 1996. A classification of forest habitat types southern Arizona and portions of the Colorado Plateau. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-GTR-287. Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, CO. 130 pp.

- Pfister, R. D. 1977. Ecological classification of forest land in Idaho and Montana. Pages 329-358 in: Proceedings of Ecological Classification of Forest Land in Canada and Northwestern USA, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

- Romme, W.H., M.L. Floyd, and D. Hanna. 2009. Historical range of variability and current landscape condition analysis: South Central Highlands section, Southwestern Colorado and Northwestern New Mexico. Col. For. Rest. Inst., Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Steele, R., R.D. Pfister, R.A. Ryker, and J.A. Kittams. 1981. Forest habitat types of central Idaho. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report INT-114. Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Ogden, UT. 138 pp.