Western Great Plains Open Freshwater Depression Wetland

Click link below for details.

General Description

The Colorado Western Great Plains Wet Meadow and Marsh Drainage Network Ecological System includes wetland types in NatureServe's Western Great Plains Open Freshwater Depression Wetland system. This Western Great Plains herbaceous-dominated wetland system includes submergent and emergent marshes, wet meadows, fens, and narrow drainages set in the headwaters of prairie streams and along small tributary drainages. Shrub patches may also occur on slope seeps and along low-gradient riparian reaches that do not support trees. These drainage networks originate in the plains or lower foothills grasslands and are fed by groundwater, seep/springs, surface runoff, precipitation, and ephemeral to intermittent channel flow. This wetland ecological system has patchy vegetation and hydrology with zones of marshes, ponds, wet meadows, salt crusts, and swales, which align with points of groundwater discharge and topographic features that support moisture retention.

Herbaceous wetland species characterize this system, including emergent species of cattail (Typha spp.), sedge (Carex spp.), spikerush (Eleocharis spp.), bullrush (Schoenoplectus spp.), rush (Juncus spp.), and cordgrass (Spartina spp.), as well as floating species such as pondweed (Potamogeton and Stuckenia spp.), arrowhead (Sagittaria spp.), duckweed (Lemna spp.), and horned pondweed (Zannichellia palustris). Nebraska sedge (Carex nebrascensis), pale spikerush (Eleocharis macrostachya), and American licorice (Glycyrrhiza lepidota) are common freshwater species; foxtail barley (Hordeum jubatum) and saltgrass (Distichlis spicata) are common in alkaline zones. Willow (Salix spp.) and other short-statured shrubs can be present with low cover.

This ecological system encompasses herbaceous drainage networks nested within the surrounding prairie ecosystems. Plains wet meadow and marshes can occur as zones of outer wet meadow and central marsh vegetation along a slope with a seasonal to perennial groundwater source. They can also occur as linear complexes of herbaceous vegetation within the stream bed, semi-permanent groundwater-fed ponds, and surface water-fed pools perched by fine-textured soil in channel depressions. Peat-accumulating wet meadows and fens, marshes, and shrub wetlands occur on or within headwaters, lowland open basins, points of spring discharge, tributary confluences, alluvial fans, and transition zones between losing and gaining stream reaches along geologic gradients. Altered examples include saturated wet meadows or marsh fringes that surround excavated or impounded ponds and small reservoirs that have been developed within drainage networks.

Diagnostic Characteristics

In eastern Colorado, these are herbaceous riparian and groundwater-fed wetland complexes of prairie headwaters and small streams. They are distinguished by low-energy dynamics that favor herbaceous vegetation on slopes or within channels with hydrology sustained by groundwater-influence, or ephemeral channels with open depressional topography that seasonally ponds surface water.

Similar Systems

Western Great Plains Closed Depression Wetland & Playa: Closed depressions and playas are distinguished by their closed topography. There can be within-channel depressions within the wet meadow and marsh drainage network system, but these depressions are clearly linked within the drainage network.

Western Great Plains Saline Depression Wetland: Some eastern Colorado headwater wetlands within the Western Great Plains Wet Meadow and Marsh Drainage Network have variable soil water alkalinity from freshwater to moderately alkaline within the same wetland complex, and this Colorado system may overlap with open (vs. closed) occurrences of Western Great Plains Saline Depressions. For Colorado, the Western Great Plains Saline Depression system is focused on saline depressions with generally closed topography.

North American Arid West Emergent Marsh: Marshes and wet meadows in the large river floodplains of eastern Colorado belong as herbaceous patch types within the Western Great Plains Floodplain system. Some of the vegetation communities also occur in the larger riparian and floodplain systems and should not be considered a separate system in that case.

Rocky Mountain Alpine-Montane Wet Meadow: The Western Great Plains Wet Meadow and Marsh Drainage Network describes wet meadows and marshes in the prairie and lower foothill grassland landscape in contrast to higher elevations.

The Colorado Western Great Plains Wet Meadow and Marsh Drainage Network Ecological System includes wetland types in NatureServe's Western Great Plains Open Freshwater Depression Wetland system. Research on the processes that influence wetland salinity and hydrology of intermittent ponds and wet meadows in eastern Colorado could increase our understanding of differences between the various plains wetland ecological systems.

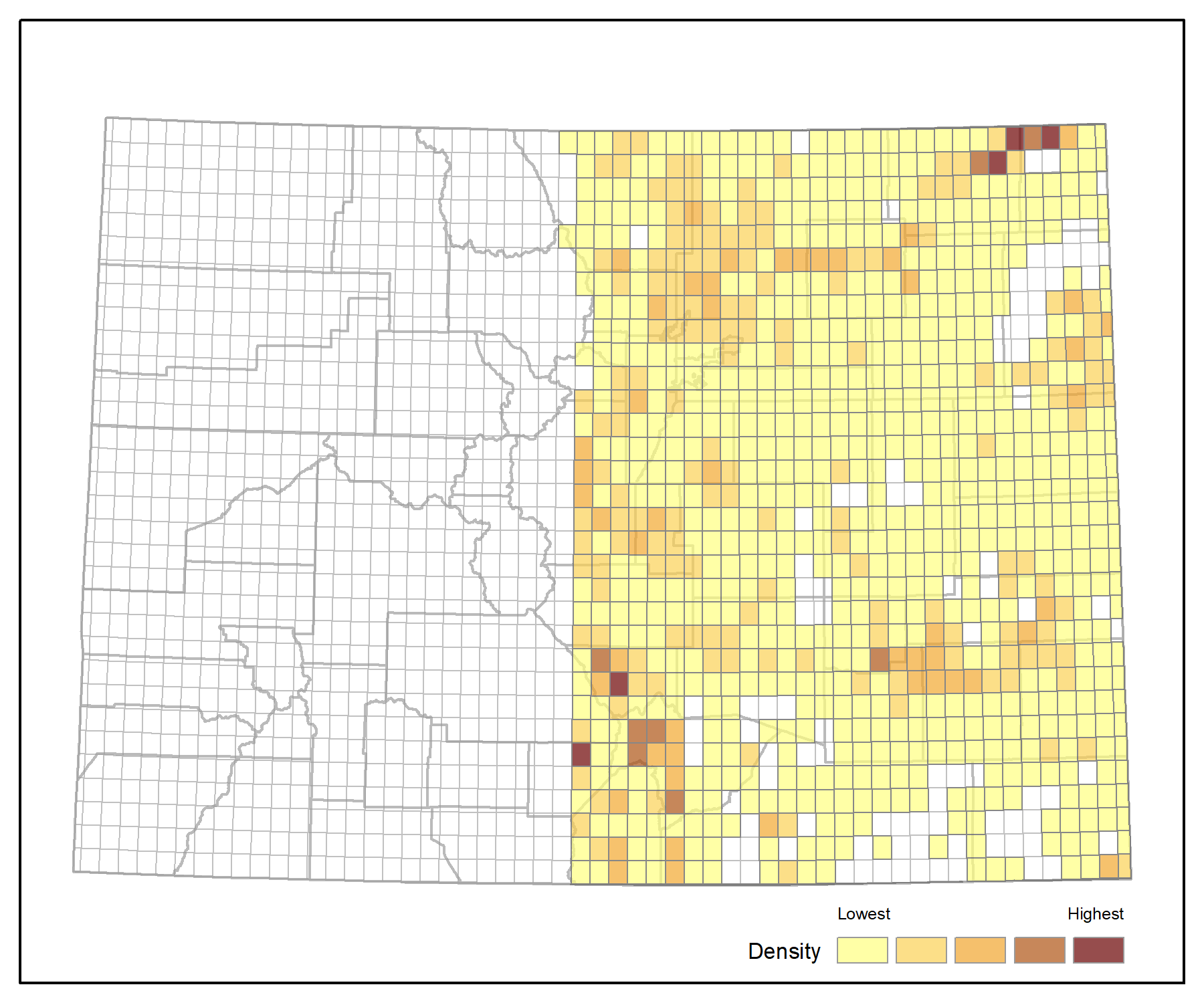

Range

This system occurs widely throughout the western Great Plains from Texas north to Canada, east of the Rocky Mountains and generally west of the Mississippi River. In eastern Colorado occurrences are widely distributed in mesic to wet prairie habitats in headwaters and small order drainages.

Ecological System Distribution

Spatial Pattern

Western Great Plains Wet Meadow and Marsh Drainage Network is a small patch type.

Environment

Set in the semi-arid Western Great Plains, in Colorado this ecological system is the drainage network of headwaters and small streams within grasslands of the state's eastern plains and lower foothills. Wetlands of this network result from distinct increases in site moisture in response to groundwater discharge and prolonged surface water retention in local depressions within drainage networks. Regional annual precipitation is generally less than 20 inches and varies with regular wet and drought year climatic cycles. Groundwater availability is a major driver in the sustenance of the wet meadow, marsh, and open depressional wetlands, many which have areas of perennial surface saturation or inundation. Seasonal wet meadow and herbaceous riparian zones alternate between wetland and non-wetland riparian areas, and surface runoff into and through in-channel depressions is a water source for the drainage network.

Vegetation

Herbaceous wetland species characterize this system, including emergent species of cattail (Typha spp.), sedge (Carex spp.), spikerush (Eleocharis spp.), bullrush (Schoenoplectus spp.), rush (Juncus spp.), and cordgrass (Spartina spp.), as well as floating species such as pondweed (Potamogeton and Stuckenia spp.), arrowhead (Sagittaria spp.), duckweed (Lemna spp.), and horned pondweed (Zannichellia palustris). Nebraska sedge (Carex nebrascensis), pale spikerush (Eleocharis macrostachya), and American licorice (Glycyrrhiza lepidota) are common freshwater species; foxtail barley (Hordeum jubatum) and saltgrass (Distichlis spicata) are common in alkaline zones. Willow (Salix spp.) and other short-statured shrubs can be present with low cover. Less typical sedge species of the Colorado plains occur in peat-accumulating plains wetlands, such as analogue sedge (Carex simulata), bottlebrush sedge (C. hystericina), Northwest Territory sedge (C. utriculata), and golden sedge (C. aurea). Dominant cover of Nebraska sedge (C. nebrascensis) or wooly sedge (C. pellita), or presence of marsh skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata), cutleaf water parsnip (Berula erecta), blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium spp.), and monkeyflower (Mimulus spp.) are often indicators of sites with organic soils. Peat-accumulating wetlands can have unique vegetation diversity and assemblages, where plains species intermix with species more typical of montane and western Colorado, including fowl mannagrass (Glyceria striata), violet (Viola spp.), avens (Geum spp.), goldenrod (Solidago spp.), and poison ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii).

- CEGL001802 Carex aquatilis Wet Meadow

- CEGL002220 Carex atherodes Wet Meadow

- CEGL001813 Carex nebrascensis Wet Meadow

- CEGL002254 Carex pellita - Calamagrostis stricta Wet Meadow

- CEGL001569 Glyceria borealis Wet Meadow

- CEGL001838 Juncus arcticus ssp. littoralis Wet Meadow

- CEGL001474 Phalaris arundinacea Western Marsh

- CEGL002002 Polygonum amphibium Aquatic Vegetation

- CEGL002030 Schoenoplectus acutus - Typha latifolia - (Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani) Sandhills Marsh

- CEGL002623 Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani Temperate Marsh

- CEGL002010 Typha (latifolia, angustifolia) Western Marsh

Associated Animal Species

Semi-permanent refuge pools within intermittent streams and saturated to shallow water plains wet meadows and marshes provide habitat for wildlife species that require perennial water. Leopard frogs (Lithobates blairi and L. pipiens) frequent perennially saturated wet meadows. Colorado plains fishes of conservation concern such as Arkansas darters (Etheostoma cragini), plains topminnows (Fundulus sciadicus), brassy minnows (Hybognathus hankinsoni), and the southern redbelly dace (Chrosomus erythrogaster) are found in within-channel groundwater-fed marshes and intermittent ponds, along with other native plains fish such as plains killifish (Fundulus zebrinus), fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas), and Iowa darters (Etheostoma exile). A targeted wildlife inventory for wet meadow and marsh drainage networks in eastern Colorado would help better understand the non-fish wildlife species of common guilds such as birds, snakes, frogs and toads, turtles, small mammals, and mollusks and other invertebrates that depend on this system.

Dynamic Processes

Along with drought and groundwater influences, processes that historically influenced wetland ecosystems in the Western Great Plains included natural disturbance regimes such as flooding and surface runoff during spring snowmelt and storm events, landslides, native ungulate grazing, fire, and beaver activity in some drainages. Groundwater depletion, stream flow alteration and floodplain disconnection, and agricultural conversion have resulted in wetland loss, and many remaining occurrences have lowered water tables. More research is needed, particularly on groundwater sources and natural disturbance regimes in herbaceous wetlands of the Colorado plains.

Few studies have examined the distribution and formation of groundwater-dependent, often peat-accumulating wetlands in the Colorado Plains. These wetland types have similarities in vegetation and hydrology to ciénegas of the southwest that are described throughout New Mexico. Multiple occurrences are documented in the Arkansas Basin Piedmont between the Palmer Divide and north of the Arkansas River in watersheds such as Chico Basin, Horse Creek, and Black Squirrel Creek. Field surveys and indicators of saturation in aerial imagery suggest that peat-accumulating wetlands are scattered throughout the Arkansas, Republican, and South Platte river basins in relatively intact grassland areas of the western Great Plains. In the larger peat-accumulating wet meadows and marshes, intermediate sandy layers that influence groundwater hydraulics indicate a dynamic formation history. Some occurrences are located in historical eolian sand dune areas, while others have shallow groundwater access from sandy alluvial sheet flow. Locations below paleo sand dune-bridges and other land formations restricting outflow, similar to the Nebraska sandhill fens, may also drive wetland formation. Steeper side-slope organic soil wetlands are also found where groundwater discharges into small depressions at the top of bank slumps, as documented in Chico Basin. Dense herbaceous graminoid wetland vegetation that transpires shallow groundwater in a basin contributes to increased site microclimate humidity and the moisture levels needed for organic soil. Hydraulic and geologic controls also play a role in retaining moisture in an otherwise semi-arid landscape.

Management

Groundwater-fed wet meadows, marshes, and fens are inherently sensitive ecosystems that need intact hydrologic and geomorphic processes to maintain wetland hydrology in regions with high evapotranspiration rates. Land use activities such as grazing, mowing, ditching, surface water impoundment, and groundwater withdrawals can compact and oxidize organic soil layers, and reduce the density and diversity of associated native plant communities. Precipitation and runoff-fed riparian depressions and drainages can experience exotic plant invasion and wetland drying if stream channels and surrounding landscapes no longer provide sufficient flow and surface runoff due to impoundments, stream flow diversions, soil tillage, and prairie conversion to irrigated or dryland crops. Ditching and filling contributing seeps and springs is common in the plains and can cause wetlands to contract and transition to uplands, often dominated by weedy plant species. Headwater seeps lose biodiversity and ecological function when excavated or impounded and transformed into ponds.

Groundwater-fed herbaceous wetlands and intact intermittent small streams are biodiversity hotspots and corridors in the Western Great Plains. They provide critical habitat for native fish and amphibians, support unique vegetation diversity, and provide refugia for many wildlife species that rely on aquatic resources within prairie grassland habitat. Groundwater dependent, organic soil wetlands in the Great Plains are estimated to be thousands of years old, but have ongoing loss by drainage and drying from a long history of cumulative land use, groundwater depletion, loss of stream-floodplain connectivity, and potentially from higher temperatures and more severe drought events due to climate change. Targeted surveys are needed to document and map the remaining groundwater-dependent wetlands of the Colorado plains, especially peat accumulating wetlands and fens. As wetland resources of high conservation value, these prairie groundwater ecosystems would benefit from fine-scale inventory across the Colorado plains, in order to monitor impacts from climate change and land/water use, and evaluate their candidacy for protection. Preserving and improving wetland condition and hydrologic and surrounding upland landscape connectivity is key for preventing further loss of wet meadow and marsh drainage networks of the Colorado plains.

Colorado Version Authors

- Colorado Natural Heritage Program Staff: CNHP Staff: Laurie Gilligan, Joanna Lemly, Karin Decker, Denise Culver, Sarah Marshall

References

- Gleason, R. A., and N. H. Euliss. 1998. Sedimentation of prairie wetlands. Great Plains Research 8(1). Paper 363.

- Gilmore, K. P., and D. G. Sullivan. 2010. Paleoenvironment and Pocket Fen Development on the Western Great Plains. Geographical Review 100: 413-429.

- Harvey, F. E., J. B. Swinehart, and T. M. Kurtz. 2007. Groundwater Sustenance of Nebraskas Unique Sand Hills Peatland Fen Ecosystems. Groundwater 45:218-234.

- Kelso, S., L. Fugere, M. K. Kummel, and S. Tsocanos. 2014. Vegetation and vascular flora of tallgrass prairie and wetlands, Black Squirrel Creek Drainage, south-central Colorado: Perspectives from the 1940s and 2011. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas 8:203-225.

- Labbe, T.R. and K.D. Fausch. 2000. Dynamics of intermittent stream habitat regulate persistence of a threatened fish at multiple scales. Ecological Applications 10: 1774-1791.

- Lauver, C.L., K. Kindscher, D. Faber-Langendoen, and R. Schneider. A classification of the natural vegetation of Kansas. The Southwestern Naturalist 44(4):421-443.

- Lemly, J., L. Gilligan, and G. Smith. 2014. Lower South Platte River Basin Wetland Profile and Condition Assessment. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Lemly, J., L. Gilligan, G. Smith, and C. Wiechmann. 2015. Colorado Natural Heritage Program Final Report: Lower Arkansas River Basin Wetland Mapping and Reference Network. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Fort Collins, CO.

- Lemly, J., L. Gilligan, and C. Wiechmann. 2017. Wetlands of the Lower Arkansas River Basin: Ecological Condition and Water Quality. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Loope, D. B., J. B. Swinehart, and J. P Mason. 1995. Dune-dammed paleovalleys of the Nebraska Sand Hills: Intrinsic versus climatic controls on the accumulation of lake and marsh sediments. Geological Society of America Bulletin 107:397-406.

- Perkin J. S., K. B. Gido, J. A. Falke, K. D. Fausch, H. C. Crockett, E. R. Johnson, and J. Sanderson. 2017. Groundwater declines are linked to changes in Great Plains stream fish assemblages. PNAS 114:7373-7378.

- Preston, T. M., R. S. Sojda, and R. A. Gleason. 2013. Sedimentation accretion rates and sediment composition in prairie pothole wetlands under varying land use practices, Montana, United States. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 68:199-211.

- Rolfsmeier, S. B., and G. Steinauer. 2010. Terrestrial ecological systems and natural communities of Nebraska (Version IV - March 9, 2010). Nebraska Natural Heritage Program, Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Lincoln, NE. 228 pp.

- Sivinski, R. 2018. Wetlands Action Plan, Arid-land spring ciénegas of New Mexico. New Mexico Environment Department, Surface Water Quality Bureau, Wetlands Program, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

- Vance, L., C. McIntyre, T. Luna. 2017. Montana Field Guide: Open freshwater depression wetland ecological system. Montana Natural Heritage Program.

- Wohl., E. D. Egenhoff, and K. Larkin. 2009. Vanishing riverscapes: A review of historical channel change on the western Great Plains. The Geological Society of America Special Paper: 451.