Western Great Plains Closed Depression Wetland and Playa

Click link below for details.

General Description

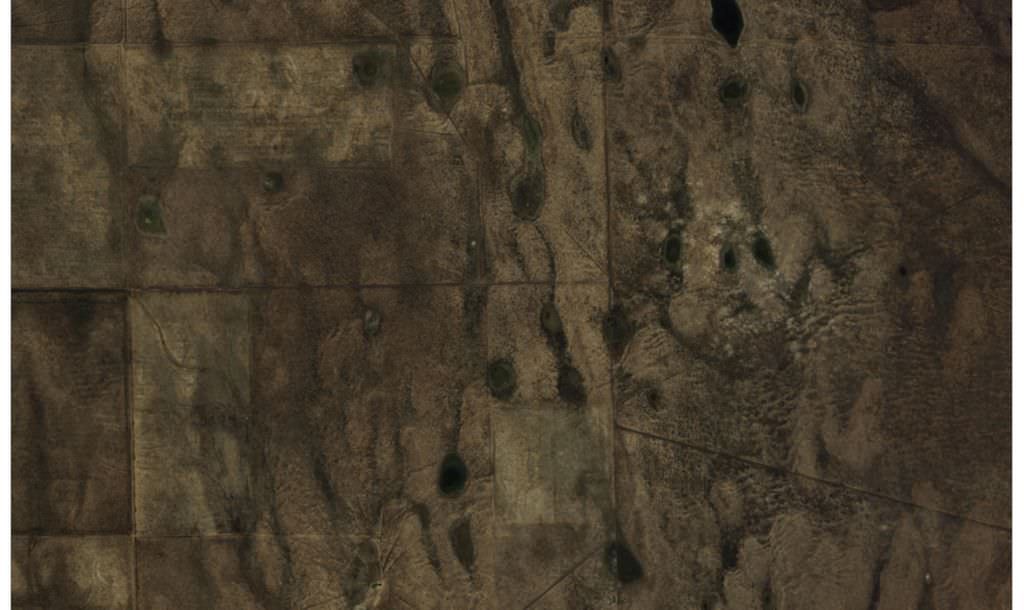

Western Great Plains Closed Depressions occur in the High Plains region of the Great Plains, which includes eastern Colorado's shortgrass prairie. Also referred to as playas or playa lakes, these closed depressions are characterized by clay-lined pond bottoms, shallow topography, and hydrology that is fed strictly from precipitation and local runoff. These wetlands are most often isolated from groundwater sources and do not have extensive watersheds, although they often occur within a larger complex of depressional wetlands. Playas experience drawdowns during drier seasons and years, and are replenished by heavy rains. They have an impermeable soil layer, usually dense hardpan clay, which restricts to water movement and induces ponding after heavy rains. These wetlands experience irregular hydroperiods and can go months or years without filling and the out ring can dry quickly after wetting. Playa vegetation commonly grows in successive zones that are associated with inundation patterns and water levels, with the most hydrophytic species occurring in the wetland center where ponding persists the longest. Plant composition and diversity also varies from site to site depending on how often it wets, surrounding land use, and micro-topography. Common vegetation in the wetter zones and playas include needle spikerush (Eleocharis acicularis), pale sprikerush (Eleocharis macrostachya), foxtail barley (Critesion jubatum), along with common forbs such as spreading yellowcress (Rorippa sinuata), wedgeleaf (Phyla cuneifolia), and woolyleaf bur ragweed (Ambrosia grayi). Shallower zones or sites that do not wet as frequently are often occupied by western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii) and buffalo grass (Buchloe dactyloides). It is not uncommon for playas to exhibit barren, cracked ground between wetting cycles, and this cracking is indicative of a healthy, functioning wetland. Threats to system integrity include hydrologic changes, overgrazing, and conversion to agricultural use.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Closed depressions are hydrologically isolated from the regional groundwater system and strictly dependent on rainwater and runoff as water sources. Impermeable clay-lined pond bottoms and shallow topography induce ponding. Vegetation density and diversity is highly dependent on wetting cycles, and often exhibits zonation. These systems are dynamic, as they respond quickly to moist and dry conditions, landscape changes, and localized used.

Similar Systems

Inter-Mountain Basins Playa: This system describes playas throughout the Intermountain West, rather than the Great Plains. Inter-mountain Basin Playas have saline soils that are intermittently flooded or are maintained by a perennially high water table. They support a sparse cover (generally < 10%) of salt-tolerant vegetation that includes both shrubs and herbs. Characteristic species of Inter-mountain Basin Playas include greasewood (Sarcobatus vermiculatus), spiny hopsage (Grayia spinosa), Lemmons alkali grass (Puccinellia lemmonii), Great Basin wildrye (Leymus cinereus), saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), and species of saltbush (Atriplex spp.).

Great Plains Prairie Pothole: Playa lakes share characteristics with prairie pothole systems, but are of dissimilar geologic origin and function. Prairie potholes are characterized as depressional wetlands carved out by glaciers located in northern Montana and Midwestern states. Like playa lakes hydrology, precipitation and snowmelt are a primary water source, but unlike playa lakes, groundwater inflow is a secondary water source. Prairie pothole soil can range from silt to clay, and topography is gradual or steep. Prairie potholes do not occur in Colorado.

Range

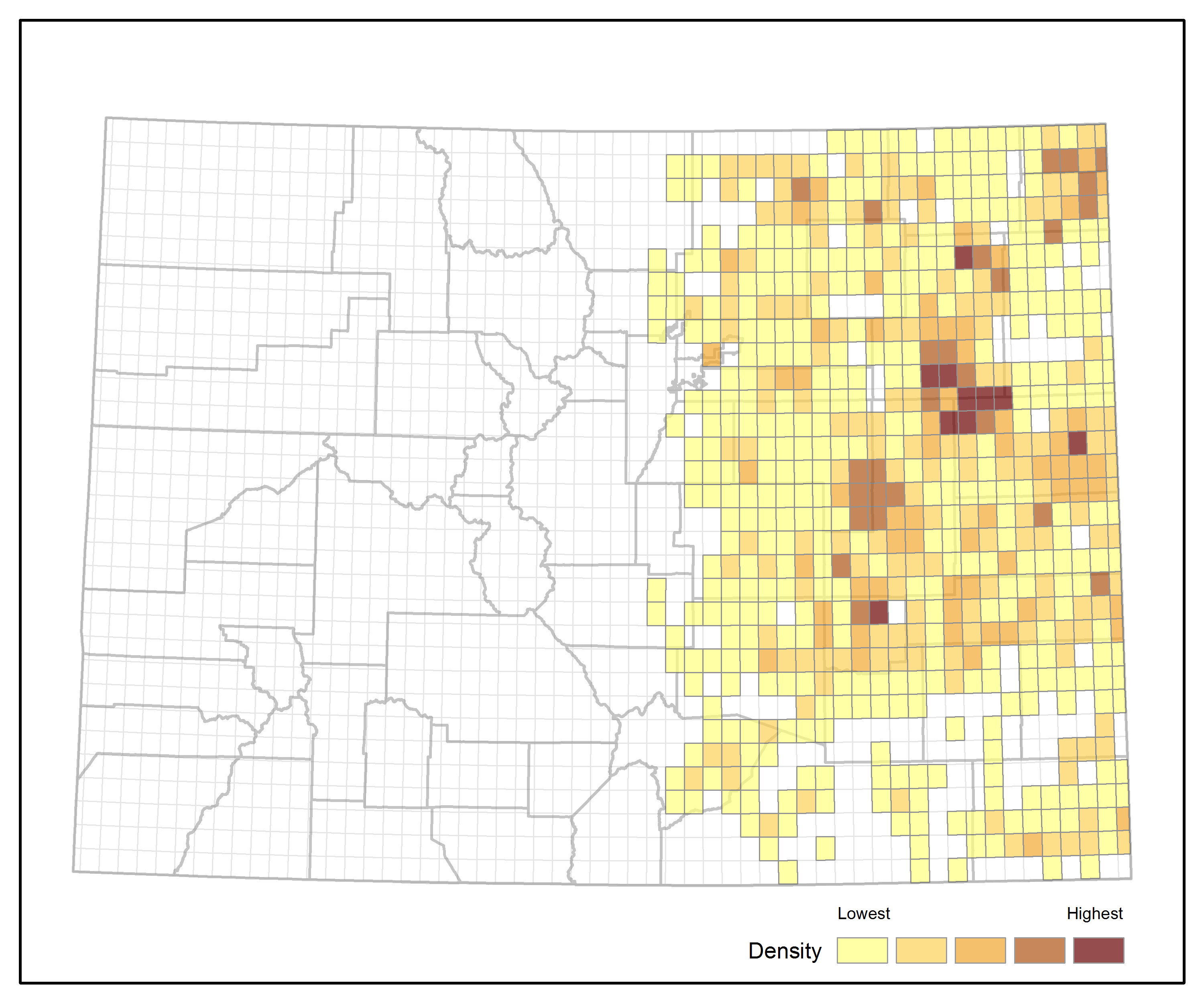

Western Great Plains Closed Depressions are located throughout the Western Great Plains, however they are most prevalent in Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma. In Colorado, they are found in the shortgrass prairie of eastern Colorado.

Ecological System Distribution

Spatial Pattern

Western Great Plains Closed Depression Wetlands are small patch wetlands.

Environment

This system is typified by depressional basins found in flat to undulating regions of the Western Great Plains in Colorado. Climate and basin physiography and morphology are key drivers of this system. Specific climatic variables most important to formation and function of these wetlands are temperature and precipitation. Climate on the Western Great Plains is semi-arid with dry, warm and sunny summers and temperatures of 95 F or above. Rainfall is below twenty inches per year, with most (70-80%) occurring in the spring and early summer during the growing season. Wind speeds are high, and their drying effects, coupled with high temperatures, cause soil drying and summer drought.

Playas form in shallow basins with an impermeable soil layer, usually dense hardpan clay, which restricts to water movement and induces ponding after heavy rains. They are temporarily or intermittently flooded and receive their water nearly exclusively as direct precipitation or surface runoff. Outflows in this system occur primarily by direct evaporation and plant transpiration, which on the plains can be high due to high temperatures and wind speed. The amount of runoff feeding each playa depends on soil hydraulic properties, soil porosity, and the size of the surrounding watershed. In northeastern Colorado, some playas may go years without filling, while others in southern Colorado may fill almost yearly. Playas experience wide water level fluctuation, which results in variation and potentially successional change of wetland plant communities.

Vegetation

Vegetation composition and structure in playas are heavily driven by wetting patterns, pond morphology, soil processes, and land use. The ephemeral nature of playa wetting impacts the vegetation community; species composition adapts as conditions change from wet to moist to dry. During pond flooding, vegetation is made up of emergent and submergent aquatic species. Playas with moist, but not inundated, soil conditions support annual species that produce high quantities of seeds. When playas are dry, forbs and grasses associated with surrounding uplands areas, and sometimes weedy species, will populate the open ground.

In regularly wetted closed depression wetlands, zonation patterns of vegetation are a common feature. Although zonation can be the result of a multitude of factors, hydrology, especially water depth and length of inundation, are the most important influences. Hydrophytic species occupy the center of these sites where ponding lasts the longest, while more facultative plant species occupy outer perimeters and many persistent species may be upland species. Common vegetation in these wetter areas include needle spikerush (Eleocharis acicularis), pale sprikerush (Eleocharis macrostachya), and hairy waterclover (Marsilea mucronata). Vegetation adapted to moist, but not inundated, zones are yellowcress (Rorippa sinuata), wedgeleaf (Phyla cuneifolia), spotted evening primose (Oenothera canescens), foxtail barley (Critesion jubatum), and woolyleaf bur ragweed (Ambrosia grayi). Transitional zones between playa and upland often include species such as buffalograss (Buchloe dactyloides), bigbract verbena (Verbena bracteata), povertyweed (Iva axillaris), woolly plantain (Plantago patagonica), short-ray prairie coneflower (Ratibida tagaetes), and western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii). Soil salinity also influences species composition and may fluctuate depending on moisture availability. For instance, foxtail barley (Critesion jubatum) is moderately salt tolerant and often occupies a zone of intermediate salinity between halophytic vegetation dominated by species such as saltgrass (Distichlis stricta) and non-saline mesic prairie vegetation. Although this zonation patterns can appear unambiguous, research shows that these growing patterns are the outcome of the complex interaction between environmental factors and seed germination, seedling recruitment dynamics, and plant dispersal.At risk species reported from this system include linear-leaf Bursage (Ambrosia linearis), Wolf's spikerush (Eleocharis wolfii).Non-native species are very common in these sites, including Russian thistle (Salsola australis), kochia (Bassia sieversiana), cheatgrass (Anisantha tectorum), oval-leaf knotweed (Polygonum arenastrum), and prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola).

- CCNHPXXX35 Buchloe dactyloides - Ratibida tagetes - Ambrosia linearis Herbaceous Vegetation

- CEGL001832 Eleocharis acicularis Marsh

- CEGL001833 Eleocharis palustris Marsh

- CPSAFRJA0A Frankenia jamesii / Achnatherum hymenoides Shrubland

- CCNHPXXX38 Frankenia jamesii / Hilaria jamesii - (Bouteloua gracilis) Shrubland

- CEGL001573 Panicum obtusum - Bouteloua dactyloides Wet Meadow

- CEGL002038 Pascopyrum smithii - Bouteloua dactyloides - (Phyla cuneifolia, Oenothera canescens) Wet Meadow

- CEGL001581 Pascopyrum smithii - Eleocharis spp. Wet Meadow

- CEGL001582 Pascopyrum smithii - Hordeum jubatum Wet Meadow

- CEGL001586 Schoenoplectus americanus - Eleocharis spp. Marsh

Associated Animal Species

Playa lakes create unique microclimates that support diverse wildlife and plant communities. When these wetlands are resupplied with water, they teem with life and provide habitat for a variety of wildlife including frogs, toads, clam shrimp, bird, and aquatic plants. During wet years playas provide nesting, feeding or resting grounds for an abundance of waterfowl, wading birds and shorebirds.

Bird species reported from prairie wetlands include Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus), Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), Green-winged Teal (Anas crecca), Cinnamon Teal (Anas cyanoptera), American Coot (Fulica americana), Blue-winged Teal (Anas discors), Killdeer (Charadrius vociferous), Common Snipe (Gallinago delicate), Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularius), Wilson's Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor), American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana), Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus), Yellow-headed Blackbird (Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus), Common Yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas), Northern Harrier (Circus cyaneus), and Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus). Two species identified as high priority for wetland habitats in this region are Northern Harrier and Short-eared Owl.

Herptofaunal species reported from this system include tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum), Great Plains toad (Anaxyrus cognatus), Woodhouse's toad (Anaxyrus woodhousei), Plains spadefoot (Spea bombifrons), and Plains Gartersnake (Thamnophis radix). Fairy Shrimp (Branchinecta potass) are also reported from this system.

Dynamic Processes

The origin of playas is not well understood. Hypotheses include dissolution of calcic soils resulting in land subsidence, bison wallowing, wind erosion, and a combination of these depositional, geomorphic and hydrological processes. These wetlands and playas are characterized by irregular hydroperiods and exhibit wide water level fluctuations; many fill with water only occasionally and dry quickly. These fluctuations in water availability often promote diverse herbaceous plant growth, with community structure and composition shaped by the timing and length of inundation or dryness.

Prairie fires were once an important component of grasslands ecosystems, occurring during the dry season when they did not damage already dormant grasses. Fire is a key disturbance influencing vegetation patterns in upland prairie ecosystems but little is known regarding its historic role in prairie playa systems. However, because playas exist in a fire-prone landscape, fires likely had impacts on playa species composition.

Management

The primary threats influencing these wetlands are hydrologic alterations, livestock grazing and conversion to agricultural use. Because playas are defined by their hydrology, impacts to their subtle topography or impermeable soils can have dramatic impacts on their function and condition. A major threat to these systems in eastern Colorado is hydrologic alterations for irrigation and stock pond purposes. The use of playas as stock ponds or detention ponds is a common practice because they form in basins and has been identified as a major impact that alters species composition. Water is divert both into and out of playas throughout the region, causing unnatural periods of inundation or drying, in turn impacting vegetation composition and seed bank dynamics. Deep pits are often dug in playas to concentrate water for agricultural uses, a practice known as "pitting. Pitting increases the duration of surface water in the center of the playa, removes water from the outer rim, and has negative implications for playa function. In addition, diverting irrigation water into playas for prolonged periods can alter the hydroperiod and can decrease characteristic plant and invertebrate species. Runoff laden with herbicides and fertilizers may impair water quality and also alters the diversity and abundance of plants and invertebrates. Other indirect hydrologic alterations are cause from soil deposition from agricultural erosion, local development that alters surface flow patterns, and pugging (mounding derived from cattle traffic).

Livestock grazing can have significant impacts on playa soil, flora, and hydroperiods. Due to the dry climate of Colorado's eastern plains, it is not uncommon for cattle to concentrate activity around playas when they are flooded or saturated, and especially if they are pitted. When the use is light and for a short duration, impacts are minimal, but occasionally, grazing is so intensive that both direct effects life herbivory and trampling, and indirect effects like nutrient enrichments through fecal and urine deposits can be damaging. When cattle trample soil during wet periods, "pugging occurs in which the clay substrate is consolidated into undulating mounds, in turn impacting the subtle topography of the pond bottom, which impacts flow and ponding dynamics. Livestock can also serve as a vector for non-native and weedy species.

Playas are strongly dependent on precipitation for their water source, therefore these depression wetlands may be especially sensitive to major shifts in temperature or precipitation due to global climate change. Increased warming and changes in the water cycle are projected. On the Great Plains, temperatures are projected to continue to increase while precipitation is anticipated to increase in the north and decrease in the south. However, due to rising temperatures and increased evaporation, projected increases in precipitation are unlikely to be sufficient to offset decreasing soil moisture and water availability in the Great Plains. Changing climate systems will only had to the stress already placed on these delicate ecosystems.

Colorado Version Authors

- Colorado Natural Heritage Program Staff: Dee Malone, Joanna Lemly, Cat Wiechmann

References

- Cariveau, A.B. and D. Pavlacky. 2009. Assessment and conservation of playas in eastern Colorado. Rocky Mountain Bird Conservancy, Brighton, Colorado.

- Carsey, K., G. Kittel, K. Decker, D. Cooper, and D. Culver. 2003. Field guide to the wetland and riparian plant associations of Colorado. Prepared for the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, Denver, CO by the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Fort Collins, CO.

- Colorado Partners in Flight. 2000. Land Bird Conservation Plan. http://www.blm.gov/wildlife/plan/pl-co-10.pdf.

- Gage, E. and D.J. Cooper. 2007. Historic Range of Variation Assessment for Wetland and Riparian Ecosystems, U.S. Forest Service, Region 2. Department of Forest, Rangeland and Watershed Stewardship, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.

- Haukos, D.A. and L.M. Smith. 1997. Common Flora of the Playa Lakes. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, Texas.

- Kingery, H. E., editor. 1998. Colorado Breeding Bird Atlas. Colorado Bird Atlas Partnership and Colorado Division of Wildlife, Denver, CO. 636 pp.

- Mutel, C.F. and J.C. Emerick. 1992. From grassland to glacier: The natural history of Colorado. Johnson Books, Boulder, Colorado.

- Seastedt, T.R. 2002. Base Camps of the Rockies: The Intermountain Grasslands. Pages 219-236 in Rocky Mountian Futures: An Ecological Perspective. J.S. Baron, ed. Island Press, Washington, DC.

- Smith, L.M. 2003. Playas of the Great Plains. University of Texas Press. Austin, Texas.