Southern Rocky Mountain Montane-Subalpine Grassland

Click link below for details.

General Description

This ecological system includes grasslands of montane to subalpine elevations in the Southern Rocky Mountains from New Mexico to Wyoming. Montane and subalpine grasslands in Colorado are generally interspersed in forest communities as park-like openings that vary in size from a few to several thousand acres. The montane grassland of South Park in Central Colorado is an exception, covering more than one million acres. This ecological system typically occurs between 2,200 and 3,350 m (7,200 and 11,000 feet) on gentle to steep slopes or more level park-like basins. A variety of factors, including fire, wind, cold-air drainage, climatic variation, soil properties, competition, and grazing have been proposed as mechanisms that maintain open grasslands and parks in forest surroundings; influential factors may vary by site. These large patch grasslands are intermixed with forests of spruce-fir, lodgepole, ponderosa pine, mixed conifers, and aspen. Within the subalpine zone, forbs tend to be more prominent at higher elevations, and shrubs at lower elevations. Associations are variable depending on site factors such as slope, aspect, precipitation, soils, and disturbance history, but generally lower elevation montane grasslands are more xeric and dominated by muhly (Muhlenbergia spp.), bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), Arizona fescue (Festuca arizonica), and Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), while upper montane or subalpine grasslands are more mesic and may be dominated by Thurber fescue (Festuca thurberi) or timber oatgrass (Danthonia intermedia).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Montane to subalpine grasslands are graminoid-dominated open areas generally within the matrix of forest and shrubland types. Occurrences are variable throughout the range of the system. Although forbs are present in most of these grasslands, they are not as prevalent as in alpine turf.

Similar Systems

Range

These grasslands of montane to subalpine elevations are found throughout the Southern Rocky Mountains from New Mexico to Wyoming.

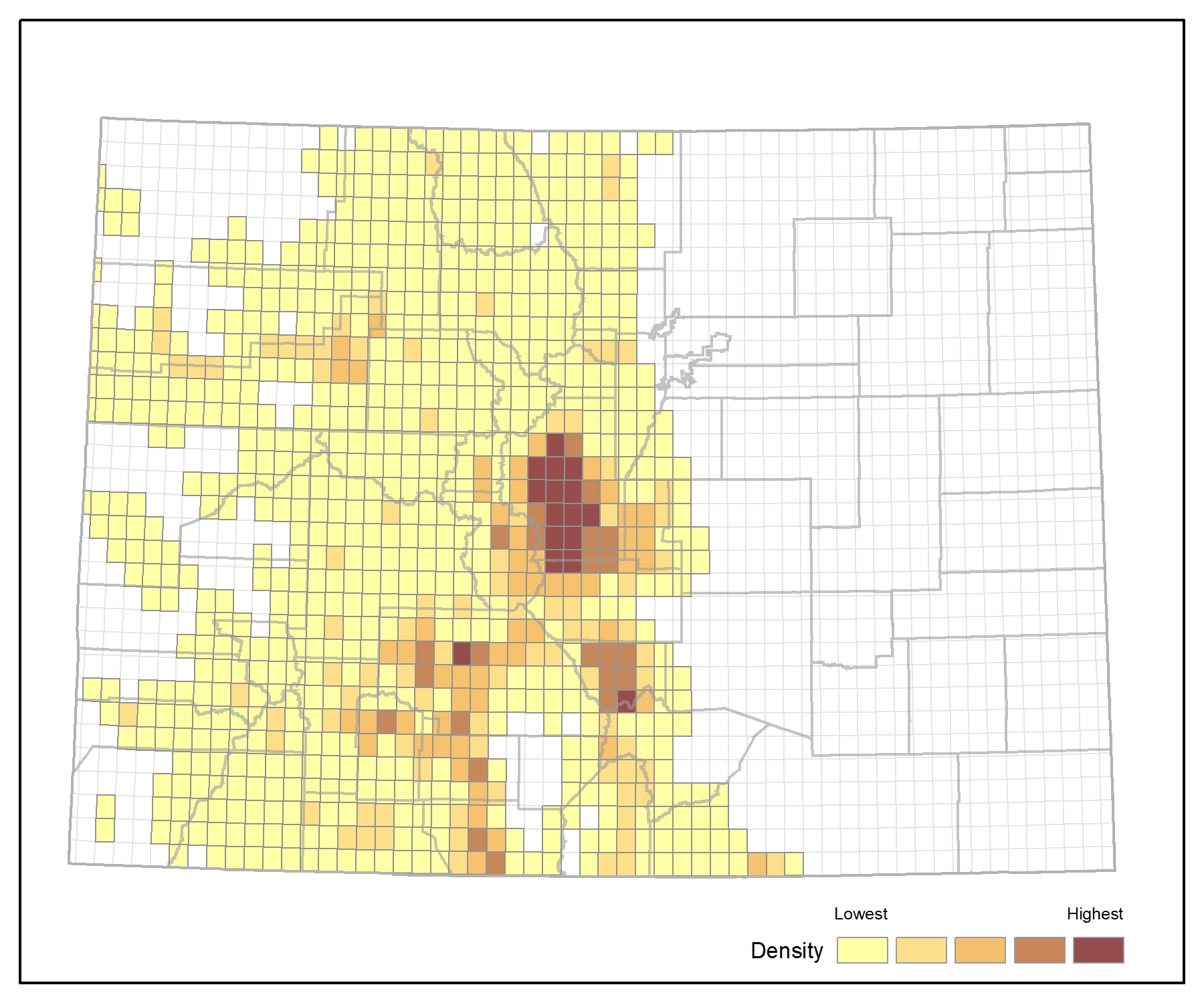

Ecological System Distribution

Spatial Pattern

Southern Rocky Mountain Montane-Subalpine Grassland is generally a large patch type, except for the extensive occurrence in South Park, Colorado.

Environment

The general climate in the range of this ecological system is characterized by cold winters and relatively cool summers, although temperatures are more moderate at lower elevations. Precipitation patterns differ between the east and west sides of the Continental Divide. In general, these grasslands experience long winters, deep snow, and short growing seasons. Average annual precipitation ranges between 20 to 40 inches, and the majority of this falls as snow. Snow cover in some areas can last from October to May, and serves to insulate the plants beneath from periodic subzero temperatures. Other areas are kept free from snow by wind. Rapid spring snowmelt usually saturates the soil, and, when temperatures rise plant growth is rapid. Precipitation during the growing season is highly variable, but provides less moisture than snowmelt. Growing seasons are short, typically from June through August at intermediate locations, although frost can occur at almost any time.

The geology of the Southern Rocky Mountains is extremely complex. Not surprisingly, soils are also highly variable, depending on the parent materials from which they were derived and the conditions under which they developed. Podzolic soils have developed on most high mountain areas as a result of cool to cold temperatures, relatively abundant moisture, and the dominant coniferous forest vegetation. In the intermingled parks and open treeless slopes or ridges, grassland soils have developed. Soil texture is important in explaining the existence of montane-subalpine grasslands. These grasslands often occupy the fine-textured alluvial of colluvial soils of valley bottoms, in contrast to the coarse, rocky material of adjacent forested slopes. Soils are often similar to prairie soils, with a dark brown A-horizon that is rich in organic matter, well drained, and slightly acidic. Other factors that may explain the absence of trees in this system are soil moisture (too much or too little), competition from established herbaceous species, cold air drainage and frost pockets, high snow accumulation, beaver activity, slow recovery from fire, and snow slides. Where grasslands occur intermixed with forested areas, the less pronounced environmental differences mean that trees are more likely to invade.

Vegetation

These large patch grasslands are intermixed with forests of spruce-fir, lodgepole, ponderosa pine, mixed conifers, and aspen. Within the subalpine zone, forbs tend to be more prominent at higher elevations, and shrubs at lower elevations. Associations are variable depending on site factors such as slope, aspect, precipitation, and latitude, but generally, lower elevation montane grasslands are more xeric and dominated by muhly (Muhlenbergia spp.), bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata), Arizona fescue (Festuca arizonica), and Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis), while upper montane or subalpine grasslands are more mesic and may be dominated by Thurber fescue (Festuca thurberi) or timber oatgrass (Danthonia intermedia). Parry's oatgrass (Danthonia parryi) is found across most of the elevational range of this system. Montane grasslands in the Colorado Front Range are often dominated by spike fescue (Leucopoa kingii) or mountain muhly (Muhlenbergia montana). In the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado, these grasslands are dominated by Festuca thurberi and other large bunch grasses. Grasses of the foothills and piedmont, such as blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), needle-and-thread (Hesperostipa comata), prairie Junegrass (Koeleria macrantha), Sandberg bluegrass (Poa secunda), western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), or little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) may be included in lower elevation occurrences. Higher, more mesic locations may support additional graminoid species including sedge (Carex spp.), alpine fescue (Festuca brachyphylla), Drummond's rush (Juncus drummondii), alpine timothy (Phleum alpinum), or spike trisetum (Trisetum spicatum). Woody species are generally sparse or absent, but occasional individuals from the surrounding forest communities may occur. Scattered dwarf-shrubs may be found in some occurrences; species vary with elevation and location. Forbs are more common at higher elevations.

- CEGL001874 Carex duriuscula Grassland

- CEGL001879 Danthonia intermedia - Solidago multiradiata Grassland

- CEGL001794 Danthonia intermedia Grassland

- CEGL001795 Danthonia parryi Grassland

- CEGL001599 Deschampsia cespitosa Wet Meadow

- CEGL005595 Elymus lanceolatus - Lupinus argenteus Grassland

- CEGL002588 Elymus lanceolatus Grassland

- CEGL001605 Festuca arizonica - Muhlenbergia filiculmis Grassland

- CEGL001606 Festuca arizonica - Muhlenbergia montana Grassland

- CEGL001614 Festuca idahoensis - Elymus trachycaulus Grassland

- CEGL001617 Festuca idahoensis - Festuca thurberi Grassland

- CEGL001618 Festuca idahoensis - Geranium viscosissimum Grassland

- CEGL001897 Festuca idahoensis Grassland

- CEGL001630 Festuca thurberi - (Lathyrus lanszwertii, Potentilla spp.) Grassland

- CEGL001631 Festuca thurberi Subalpine Grassland

- CEGL001479 Leymus cinereus Alkaline Wet Meadow

- CEGL001780 Muhlenbergia filiculmis Grassland

- CEGL001647 Muhlenbergia montana - Hesperostipa comata Grassland

- CEGL001646 Muhlenbergia montana Grassland

- CEGL002363 Muhlenbergia pungens Grassland

- CEGL001578 Pascopyrum smithii - Bouteloua gracilis Grassland

- CEGL005654 Pascopyrum smithii Southern Rocky Mountain Grassland

- CEGL001925 Poa fendleriana Grassland

- CEGL001657 Poa secunda Moist Meadow

- CEGL001676 Pseudoroegneria spicata - Poa fendleriana Grassland

- CEGL001660 Pseudoroegneria spicata Grassland

Associated Animal Species

Pocket gophers (Thomomys spp.) and other small mammals are common in these grasslands, which also provide forage areas for elk (Cervus elaphus). Typical bird species are Vesper sparrow, Mountain Bluebird (Sialia currucoides), Horned Lark (Eremophila alpestris), and Brewer's Blackbird (Euphagus cyanocephalus).

Dynamic Processes

A variety of factors, including fire, wind, cold-air drainage, climatic variation, soil properties, competition, and grazing have been proposed as mechanisms that maintain open grasslands and parks in forest surroundings. Observations and repeat photography studies in sites throughout the southern Rocky Mountains indicate that trees do invade open areas, but that the mechanisms responsible for this trend may differ from site to site. Climatic variation, fire exclusion, and grazing appear to interact with edaphic factors to facilitate or hinder tree invasion in these grasslands.

Pocket gophers (Thomomys spp.) are a widespread source of disturbance in montane-subalpine grasslands. The activities of these burrowing mammals result in increased aeration, mixing of soil, and infiltration of water, and are an important component of normal soil formation and erosion. In addition, below-ground herbivory of pocket gophers can restrict tree establishment. The interaction of multiple factors indicates that management for the maintenance of these montane and subalpine grasslands may be complex.

Floristic composition in these grasslands is influenced by both environmental factors and grazing history. Grazing is generally believed to lead to the replacement of palatable species with less palatable ones more able to withstand grazing pressure. In general, palatable grasses are replaced by nonpalatable forbs or shrubs under cattle grazing, while palatable forbs are characteristically absent from grasslands with a long history of sheep use. Annual species are uncommon except on heavily disturbed areas.

Management

Grazing by domestic livestock may act to override or mask whatever natural mechanism is responsible for maintaining an occurrence. Montane-subalpine grasslands were first grazed by domestic livestock beginning in the late 1800's. After lower-elevation, more accessible rangelands were overstocked in the 1870's and 1880's, use of montane and subalpine grasslands increased dramatically. By the turn of the century nearly all grazable land was being utilized, and much was already overgrazed. As National Forests were established following the Organic Administration Act of 1897, regulation of grazing on these high elevation grasslands was instituted. Use levels peaked near the end of the first World War, and current use levels are substantially lower than the highest previous level.

Warmer and drier conditions are likely to facilitate the spread of invasive species, and may allow woody species to establish in grasslands. An increase in forest fire activity under future conditions may allow grassland to expand into adjacent burned areas. Montane grasslands are moderately vulnerable to the effects of climate change by mid-century. Primary contributing factors are vulnerability of these area to invasive species, and the generally highly disturbed condition of occurrences, both of which are likely to interact with the significant increases in temperature across much of the distribution of the habitat in Colorado to reduce resilience of these habitats. Research in New Mexico suggests that both changing disturbance regimes and climatic factors are linked to tree establishment in some montane grasslands. Increased tree invasion into montane grasslands was apparently linked to higher summer nighttime temperatures, and less frost damage to tree seedlings; this trend could continue under projected future temperature increases. Increased disturbance may also facilitate the continued spread of introduced exotic species as climate conditions change. The interaction of multiple factors indicates that management for the maintenance of these montane and subalpine grasslands may be complex.

References

- Anderson, M.D. and W.L. Baker. 2005. Reconstructing landscape-scale tree invasion using survey notes in the Medicine Bow Mountains, Wyoming, USA. Landscape Ecology 21:243-258.

- Brown, D.E., editor. 1994. Biotic Communities: Southwestern United States and Northwestern Mexico. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

- Cantor, L.F. and T.J. Whitham. 1989. Importance of belowground herbivory: pocket gophers may limit aspen to rock outcrop refugia. Ecology 70:962-970.

- Coop, J.D. and T.J. Givnish. 2007. Spatial and temporal patterns of recent forest encroachment in montane grasslands of the Valles Caldera, New Mexico, USA. Journal of Biogeography 34:914-927.

- Daubenmire, R.F. 1943. Vegetational zonation in the Rocky Mountains. Botanical Review 9:325-393.

- Ellison, L. 1946. The pocket gopher in relation to soil erosion on mountain range. Ecology 27(2):101-114.

- Jamieson, D.W., W.H. Romme, and P. Somers. 1996. Biotic communities of the cool mountains. Chapter 12 in The Western San Juan Mountains : Their Geology, Ecology, and Human History, R. Blair, ed. University Press of Colorado, Niwot, CO.

- Knight, D.H. 1994. Mountains and plains: Ecology of Wyoming landscapes. Yale University Press, New Haven, MA. 338 pp .

- Paulsen, H.A., Jr. 1969. Forage values on a mountain grassland-aspen range in western Colorado. Journal of Range Management 22:102-107.

- Paulsen, H.A., Jr. 1975. Range management in the central and southern Rocky Mountains: a summary of the status of our knowledge by range ecosystems. USDA Forest Service Research Paper RM-154. Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, USDA Forest Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Peet, R. K. 1981. Forest vegetation of the Colorado Front Range: composition and dynamics. Vegetatio 45:3-75.

- Peet, R.K. 2000. Forests and meadows of the Rocky Mountains. Chapter 3 in North American Terrestrial Vegetation, second edition. M.G. Barbour and W.D. Billings, eds. Cambridge University Press.

- Schauer, A.J., B.K. Wade, and J.B. Sowell. 1998. Persistence of subalpine forest-meadow ecotones in the Gunnison Basin, Colorado. Great Basin Naturalist 58:273-281.

- Smith, D.R. 1967. Effects of cattle grazing on a ponderosa pine-bunchgrass range in Colorado. USDA Forest Service Technical Bulletin No. 1371. Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, USDA Forest Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Stohlgren, T.J., L.D. Schell, and B. Vanden Huevel. 1999. How grazing and soil quality affect native and exotic plant diversity in rocky mountain grasslands. Ecological Applications 9:45-64.

- Turner,G.T. and H.A. Paulsen, Jr. 1976. Management of mountain grasslands in the central Rockies:The status of ourknowledge. USDA Forest Service Research Paper RM-161, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins,Colorado.

- Zier, J.L. and W.L. Baker. 2006. A century of vegetation change in the San Juan Mountains, Colorado: An analysis using repeat photography. Forest Ecology and Management 228:251262.