Colorado Plateau Hanging Garden

Click link below for details.

General Description

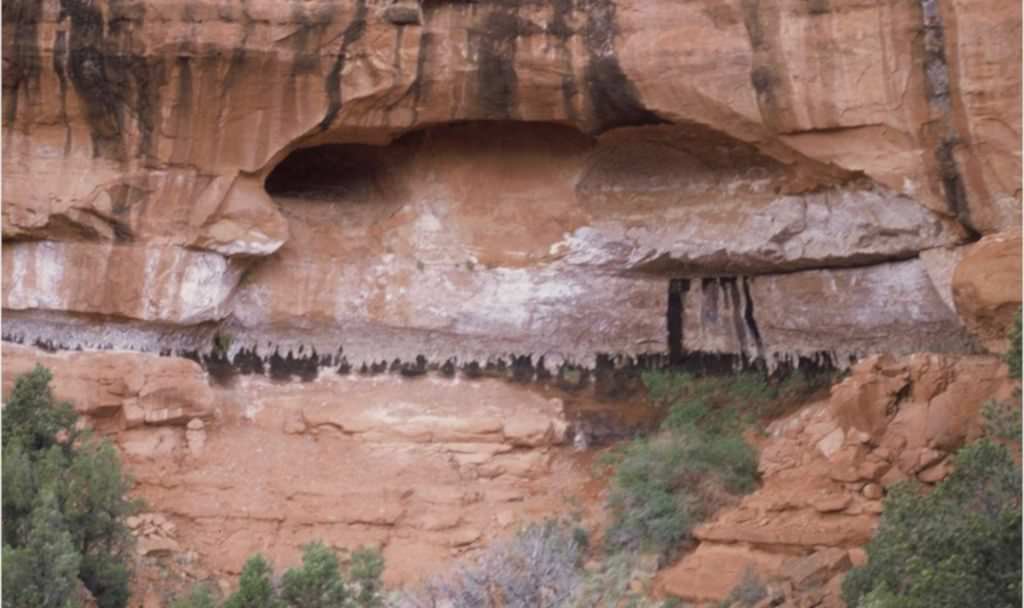

Hanging gardens are a small patch community type in the canyons of western Colorado. These highly restricted environments are found in canyonlands with perennial water sources (seeps) that form pocket wetlands, often with vegetation draped across wet cliff faces. Hanging gardens are variable in form depending on how water moves through joints in the surrounding rock formations. Most hanging gardens are dominated by herbaceous plants, and a number of regional endemic species are found in these communities. Common species include maidenhair fern (Adiantum capillus-veneris), Eastwood's monkeyflower (Mimulus eastwoodiae), seep monkeyflower (Mimulus guttatus), Purpus' sullivantia (Sullivantia hapemanii var. purpusii), oil shale columbine (Aquilegia barnebyi), and Mancos columbine (Aquilegia micrantha). In Colorado this system includes hanging gardens of the Utah High Plateau ecoregion, which differ somewhat in geology and species composition from those of the Colorado Plateau to the south.

Diagnostic Characteristics

Colorado Plateau Hanging Garden ecological systems are small communities of hydrophytic plants that occupy alcoves, seeps and springs in canyon walls where they grow on permanently wet soil and wet rock surfaces that originate from seeps. Typical plant species include southern maidenhair fern (Adiantum capillus-veneris), northern maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum), Eastwood's monkeyflower (Mimulus eastwoodiae), common large monkeyflower (M. guttatus), and Mancos columbine (Aquilegia micrantha). Utah High Plateaus examples are associated with waterfalls or cliff seeps, with typical species including Purpus' sullivantia (Sullivantia hapemanii), oil shale columbine (Aquilegia barnebyi), common large monkeyflower (M. guttatus), and an abundant moss component.

Similar Systems

Hanging gardens of the Utah High Plateaus have not been fully described as a separate ecological system, and are included here. The diversity of vegetation is generally higher in Colorado Plateau hanging gardens than in Utah High Plateaus hanging gardens. Occurrences in the Utah High Plateau ecoregion are associated with calcareous formations, especially shales of the Green River Formation, while those of the Colorado Plateau ecoregion are associated with massive sandstone deposits such as the Navajo and Entrada.

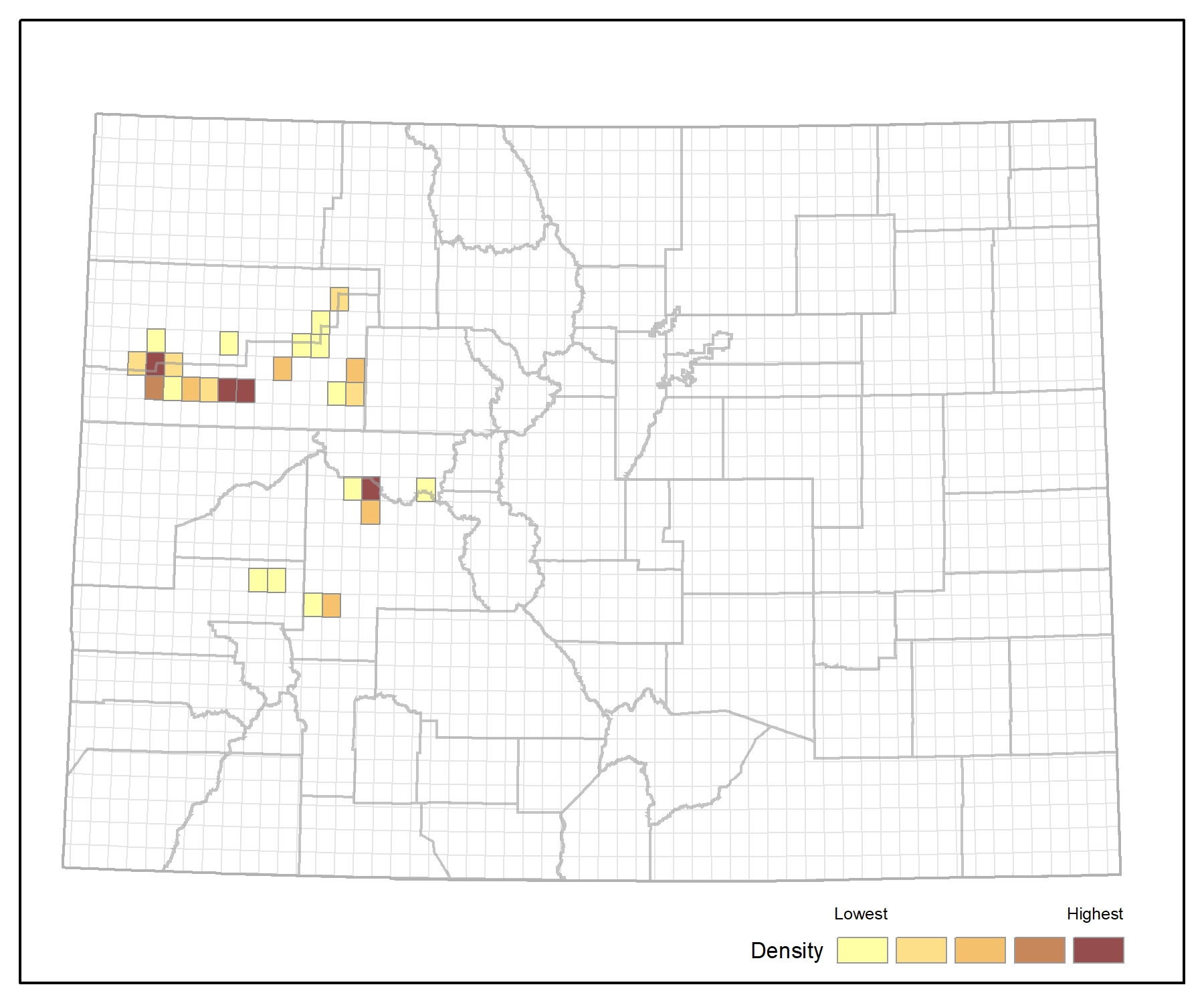

Range

Hanging gardens are found in canyons of the Colorado Plateau and Utah High Plateaus ecoregions. Colorado occurrences are restricted to the west slope. Colorado Plateau types are typical of sandstone canyons, while Utah High Plateaus types are generally restricted to the Green River Formation in the oil shale region, especially on the Roan Plateau.

Ecological System Distribution

Spatial Pattern

Colorado Plateau Hanging Gardens are a small patch system.

Environment

Much of the Colorado Plateau is a landscape formed from thick horizontal sedimentary strata where the perpetual action of wind and water has carved complex canyons that provide habitat for hanging gardens. The hanging garden environment is characterized by perennially wet rock walls and/or wet shallow, colluvial soils at a seep from bedrock. Seeps occur where groundwater percolating through the stone reaches the surface along joints between impervious strata. Water that supplies the springs and seeps is derived from local sandstone aquifers that are primarily supplied by winter precipitation. Hanging gardens can occur in a variety of sites, typically where erosion has modified the steepness of the canyon wall, such as at alcoves or at seeps and springs in canyon walls. Often these locations are in wet theater-headed valleys formed by enhanced weathering and erosion due to water seepage.

In the northern portion of the Colorado Plateau, however, and in the Southern Rocky Mountains, hanging gardens are associated with springs, seeps, and waterfalls formed in calcareous shales, primarily those of the Green River Formation. The vegetation grows in the cracks behind and beside the waterfall, where it often completely fills every available ledge. In the seeps adjacent to waterfalls and in the splash zones at the base of falls, the substrate is saturated during most of the growing season. Here the vegetation is continually wet, at least near the bases of the plants, and water can very commonly be seen dripping from leaves, exposed roots, and old stems. Although large occurrences of these hanging gardens are primarily associated with waterfalls, smaller occurrences can occur along cliff seeps above streams, especially in the Roan plateau area.

Vegetation

Hanging gardens are moist islands of vegetation embedded with expanses of bedrock. These moisture-loving plant communities can develop in these sites because of the microclimate created by groundwater seepage zones and related erosional processes that produce the physical hanging garden habitat characterized by perennially wet rock walls and/or wet, subirrigated colluvial soils. Often species diversity is low, although it is typically much greater in the gardens on the Colorado Plateau than in those of the Utah High Plateaus. Species may be shared with nearby riparian vegetation, but there are a series of species, including algae, that are unique to hanging gardens. The classic alcove type of hanging garden consists of an overhanging back wall, a vaulted face wall, a detrital slope, and a plunge basin. The back and face walls support clinging plants such as southern maidenhair fern (Adiantum capillus-veneris) and Eastwood's monkeyflower (Mimulus eastwoodiae). Species growing at the base of these seeps where soil development can occur include golden-fruit sedge (Carex aurea), Mancos columbine (Aquilegia micrantha), ditch reedgrass (Calamagrostis scopulorum), giant helleborine (Epipactis gigantea), and tapered rosette grass (Dichanthelium acuminatum). A fringing margin of netleaf hackberry (Celtis laevigata var. reticulata) and Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii) often occurs outward from the footslope where the plants tend to conceal the alcove base. In the Utah High Plateaus gardens, the dominants are usually Purpus' sullivantia (Sullivantia hapemanii var. purpusii) and Barneby's columbine (Aquilegia barnebyi) with large monkeyflower (Mimulus guttatus) common.

- CEGL002592 Aquilegia micrantha - Calamagrostis scopulorum Hanging Garden

- CEGL002729 Aquilegia micrantha - Mimulus eastwoodiae Hanging Garden

- CEGL002762 Aquilegia micrantha Hanging Garden

- CEGL002751 Calamagrostis scopulorum Seep Hanging Garden

- CPWCCAAQ0A Catabrosa aquatica - Mimulus ssp. Spring Wetland

- CEGL005305 Mimulus guttatus - (Mimulus spp.) Seep

- CCNHPXXX36 Sullivantia hapemanii - (Aquilegia barnebyi) Herbaceous Vegetation

- CEGL005509 Sullivantia hapemanii - Mimulus spp. Wet Rock Vegetation

Associated Animal Species

The hydrology that enables the development of hanging gardens also provides resources for a wide diversity of native wildlife. Hanging gardens are also "hot spots of biodiversity, with many species of endemic terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates as well as birds, mammals, and amphibians. Animal species associated with hanging gardens include Canyon Wren (Catherpes mexicanus), Rock Wren (Salpinctes obsoletus), Say's Phoebe (Sayornis saya), canyon treefrog (Hyla arenicolor), red-spotted toad (Anaxyrus punctatus), Colorado chipmunk (Neotamias quadrivittatus) bushy-tailed woodrat (Neotoma cinerea), desert woodrat (Neotoma lepida), Mexican woodrat (Neotoma mexicana), and Colorado forestfly (Malenka coloradensis).

Dynamic Processes

The type of garden is determined by the nature of the geological formation and the presence or absence of joint systems. In general, the hanging gardens result from ancient swales or valleys in a sand dune-swale system that developed between the Cretaceous and Pennsylvanian periods (65-310 mya). The formations with the greatest development are the Navajo and Entrada, both of them cross-bedded, massive formations composed of wind-blown sand and containing ancient pond bottoms that serve as impervious bedding planes. Water percolating through the porous rock encounters the ancient bedding planes, still impervious and capable of holding water. When filled to overflowing, these bedding planes carry the water downward to the next bedding plane beneath or to another impervious stratum at the base of the formation. Joint systems within the rock act as passageways for water. Where the joint systems are exposed along canyon walls the water flows over the moist surfaces.

The complexity of the plant community in a hanging garden is a function of the quantity and quality of water, developmental aspects, and ability of plant species to disperse to it. Gardens vary in size, aspect, exposure to the elements, water quantity and quality, number of bedding planes, and amount of light received. Water quality, in some degree, controls the type of plants found in hanging gardens, which is dictated by the nature of the formations through which the water passes. Water is often of drinkable quality, but may be saline or laden with calcium, which results in tufa deposits in the gardens.

Management

Primary threats to this system are invasive plant species, trampling and hydrologic alteration. Some gardens are currently threatened by invasive exotics such as tamarisk (Tamarix chinensis). Historically, springs on the Colorado Plateau have been widely used as domestic and livestock water sources. At some springs the remnants of previous land use, such as water diversions and spring boxes, are still visible, and their impacts, including altered vegetation composition, are still evident. The effects of visitor use, including water pollution, social trailing, and trampling, are also a concern in some areas. For instance, the Mancos columbine-Eastwood monkeyflower plant association (G2G3/S2S3) occurs on seeping sandstone walls and alcoves where its location generally protects it from disturbance, but disturbance to the water source can eliminate the association.

Climate change, especially altered precipitation regimes, can change groundwater availability, resulting in altered spring flow and habitat availability. If winter precipitation declines, this may adversely affect the aquifers and their associated wildlife, including the hanging gardens. Climate change models applied to the Colorado Plateau predict significant changes in the next 30-100 years. By 2090, precipitation is predicted to decline by as much as 5 percent across the region. This reduction, while apparently small, is critical when looking at the already low amounts of precipitation most of the region experiences. Any declines in precipitation are likely to increase drought stress in existing native plant communities resulting in a greater susceptibility of existing ecosystems to replacement by noxious and other invasive weedy species.

References

- Carsey, K., G. Kittel, K. Decker, D. Cooper, and D. Culver. 2003. Field guide to the wetland and riparian plant associations of Colorado. Prepared for the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, Denver, CO by the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Fort Collins, CO.

- Fowler, J.F., N.L. Stanton and R.L. Hartman. 2007. Distribution of Hanging Garden Vegetation Associations on the Colorado Plateau, USA. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas 1:585-607.

- Malanson, G.P. 1980. Habitat and plant distributions in hanging gardens of the Narrows, Zion National Park, Utah. Great Basin Naturalist 40:178-182.

- Fowler, J.F., N.L. Stanton, R.L. Harman and C.L. May. 1995. Level of Endemism in Hanging Gardens of the Colorado Plateau. Proceedings of the second biennial conference on research in Colorado Plateau National Parks; Transactions and Proceedings Series NPS/NRNAU/NRTP-95/11.

- May, C.L. 1997. Geoecology of the Hanging Gardens: Endemic Resources in the GSENM. Pp 245-257 in Learning from the Land: Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Science Symposium Proceedings : November 4-5, 1997, Southern Utah University, Cedar City, Utah.

- May, C.L., J.F. Fowler, and N.L. Stanton. 1993. Geomorphology of the Hanging Gardens of the Colorado Plateau. Pp. 3-24 in Proceedings of the 2nd Biennial Conference on Research in Colorado Plateau National Parks. October 25-28, 1993, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ.

- Welsh, S.L. 1989. On the distribution of Utah's hanging gardens. Great Basin Naturalist 49(1):1-30.

- Welsh, S.L. and C.A. Toft. 1981. Biotic communities of hanging gardens in southeastern Utah. National Geographic Society Research Reports 13: 663-681.