Western Great Plains Floodplain

Click link below for details.

General Description

The Western Great Plains Floodplain system is confined to the floodplains of medium and large rivers of the Western Great Plains. In Colorado, this system is limited to the South Platte and Arkansas Rivers and Fountain Creek. These are the perennial big rivers of the region and their hydrology is largely driven by snowmelt in the mountains instead of local precipitation events. Seasonal and larger episodic flooding events (every 5-25 years) redistribute alluvial soils and are essential to the maintenance of this system. Plains floodplains are characterized by a linear mosaic of wetland and riparian communities that are linked by soils and flooding regime. Dominant communities include open to closed gallery forests, dense shrublands along the river's edge, open wet and mesic meadows and sparsely vegetated gravel and sand flats. Dominant native woody species include plains cottonwood (Populus deltoides) and willow (Salix spp.) species. Native herbaceous cover is a mix of saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), and tallgrass species, including switchgrass (Panicum virgatum and P. obtusum), intersperses with pockets of marsh vegetation. Invasion of non-native species is one consequence of anthropogenic alteration of the plains floodplain system. These areas have often been subjected to heavy grazing and/or agriculture and can be heavily degraded. In most cases, the majority of the wet meadow and prairie communities may be extremely degraded or extirpated from examples of this system and less desirable or exotic grasses and forbs have displaced the native understory. In many locations, the canopy also contains or is dominated by non-native woody species, including tamarisk (Tamarix spp.) and Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia).

Diagnostic Characteristics

Seasonal and larger episodic flooding are key drivers of floodplain systems and act to differentiate floodplains from other wetland and riparian ecosystems. Meandering channels create dynamic alluvial bars, depressions. Vegetation is a characterized by mosaic of floodplain forests, wet meadows and sparsely vegetated gravel and sand flats and occurs in zones reflective of past deposition and flooding.

Similar Systems

Range

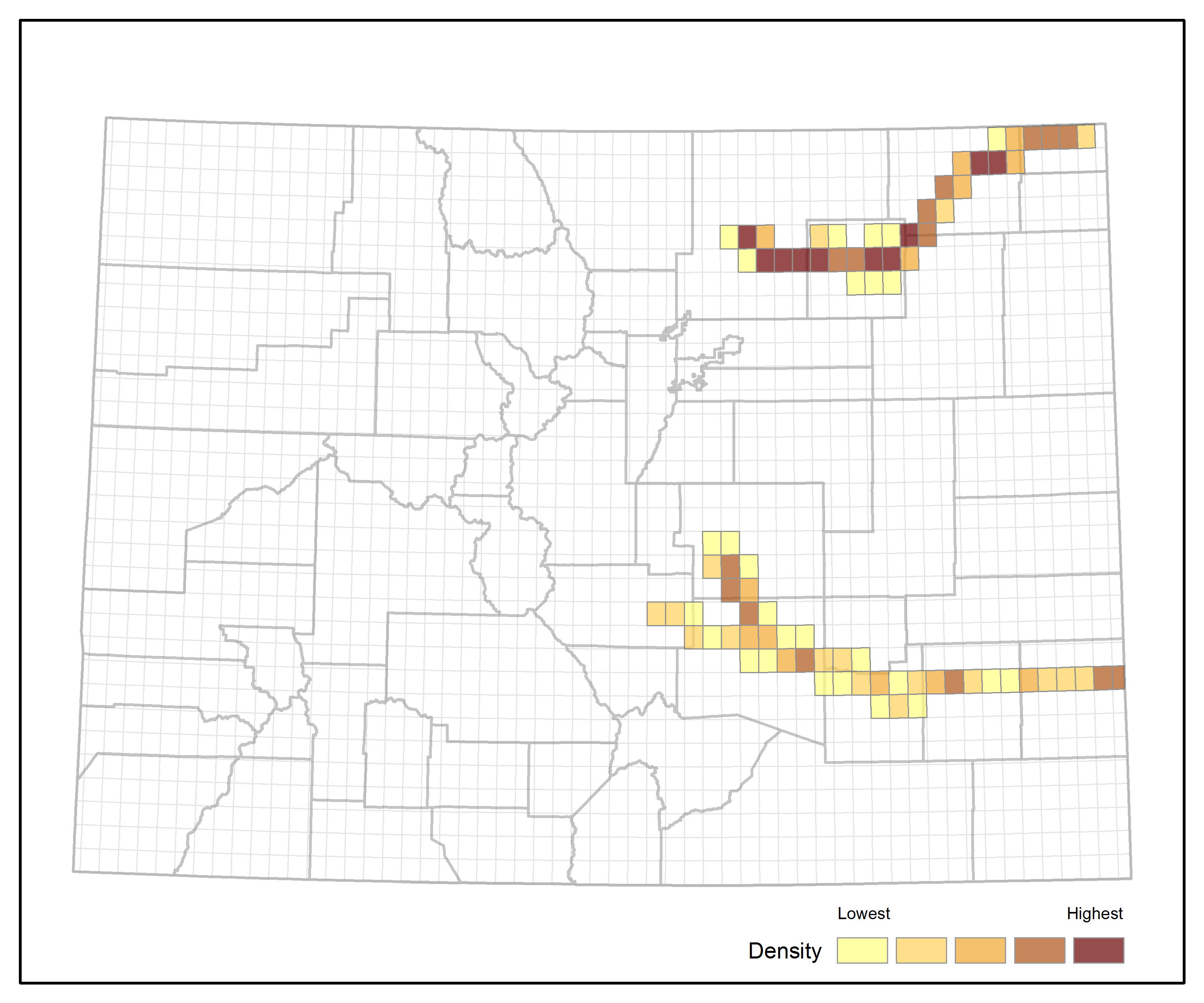

This system is found along the major river floodplains of the Western Great Plains (Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas) on the middle to lower reaches of the North and South Platte, Platte, Arkansas, Republican and Canadian rivers. Colorado occurrences are on the South Platte and Arkansas rivers.

Ecological System Distribution

Spatial Pattern

Western Great Plains Floodplain is a linear system.

Environment

In Colorado, the Western Great Plains Floodplain system occurs primarily along the South Platte and Arkansas Rivers, as well as Fountain Creek. The floodplains adjacent to these large rivers can be physically complex with long periods of seasonal flooding, lateral channel migration, oxbow lakes in old river channels, and diverse wetland communities. The surrounding upland terrain varies from level to gently rolling hills but also contains some deep canyons and dramatic escarpments, buttes, mesas and volcanic peaks.

The Colorado plains are situated in the rain shadow of the Rockies causing dry, warm and sunny summers with temperatures often 95o F or above. Rainfall is below twenty inches per year, with 70-80% falling in the spring and summer during the growing season. Wind speeds are high, and their drying effects, together with high temperatures, cause soil drying and summer drought. Climate in floodplain wetlands is similar to the surrounding upland habitat, however the increased cover from the tree canopy moderates intense winds and sunlight and provides protected habitat to support a diverse faunal community.

Dynamic and episodic flood events are the key drivers of floodplain systems, with hydrology largely driven by snowmelt from the mountains rather than local precipitation events. Floodplains of these rivers are continually changing in response to dynamic overbank flows. Where streams remain un-channeled they meander across their floodplain creating depressions, oxbows, backwaters, ponds, and sloughs that support a complex mosaic of wetland and non-wetland riparian vegetation. Flooding from the stream channel recharges many alluvial aquifers and as stream flow decreases, the alluvial aquifer begins to recharge stream flow. Floodplain soils are young and moist, with a high water table and poor drainage. They are primarily formed from relatively recent deposits of coarse gravel, silt and sand.

Vegetation

The Western Great Plains Floodplain system is a mosaic of wetland and non-wetland plant communities characterized by cottonwood gallery forests, willow shrublands, and herbaceous communities responding to dynamic and meandering rivers. Common native tree species include plains cottonwood (Populus deltoides ssp. monilifera), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica var. lanceolata), and peach-leaf willow (Salix amygdaloides). Common native shrubs include narrowleaf willow (Salix exigua), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), and western snowberry (Symphoricarpos occidentalis). Native graminoid species include switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), prairie cordgrass (Spartina pectinata), sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus), western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), slender wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus), blue grama (Chondrosum gracile), inland saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), foxtail barley (Hordeum jubatum), annual rabbitsfoot grass (Polypogon monspeliensis), with wetland sedges (Carex spp.), bulrushes (Schoenoplectus spp.), and cattail (Typhya latifolia and T. angustifolia) in wetter zones. Native forb species include Cuman ragweed (Ambrosia psilostachya), showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa), thymeleaf sandmat (Chamaesyce serpyllifolia), Canadian horseweed (Conyza canadensis), American licorice (Glycrrhiza lepidota), common sunflower (Helianthus annuus), and California nettle (Urtica gracilis).

Alteration of the flooding regime and disturbances such as overgrazing and agriculture have enabled the invasion of numerous non-native plant species. In the South Platte Basin, native cottonwoods remain the dominant woody canopy, but the understory composition of most floodplain systems is dominated by cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), barnyard grass (Echinochloa crus-galli), smooth brome (Bromus inermis), and quackgrass (Elytrigia repens). Common non-native forbs include kochia (Bassia sieversiana), Russian-thistle (Salsola australis), Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense), curly dock (Rumex crispus), poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), lambsquarters (Chenopodium album), sweetclover (Melilotus spp.), and moist sowthistle (Sonchus arvensis ssp. uliginosus). In the Arkansas Basin, dense tamarisk now dominates the canopy of most floodplain systems, despite eradication efforts.

- CEGL001813 Carex nebrascensis Wet Meadow

- CEGL000659 Populus deltoides - (Salix amygdaloides) / Salix (exigua, interior) Floodplain Woodland

- CEGL002017 Populus deltoides - (Salix nigra) / Spartina pectinata - Carex spp. Floodplain Woodland

- CEGL000939 Populus deltoides (ssp. wislizeni, ssp. monilifera) / Distichlis spicata Riparian Woodland

- CEGL002685 Populus deltoides (ssp. wislizeni, ssp. monilifera) / Salix exigua Riparian Woodland

- CEGL005977 Populus deltoides (ssp. wislizeni, ssp. monilifera) / Sporobolus airoides Flooded Woodland

- CEGL002649 Populus deltoides / Carex pellita Floodplain Woodland

- CEGL000678 Populus deltoides / Muhlenbergia asperifolia Flooded Forest

- CEGL001454 Populus deltoides / Panicum virgatum - Schizachyrium scoparium Floodplain Woodland

- CEGL005024 Populus deltoides / Pascopyrum smithii - Panicum virgatum Floodplain Woodland

- CEGL000660 Populus deltoides / Symphoricarpos occidentalis Floodplain Woodland

- CEGL005656 Salix exigua / Gravel Bar Wet Shrubland

- CEGL001203 Salix exigua / Mesic Graminoids Western Wet Shrubland

- CEGL002030 Schoenoplectus acutus - Typha latifolia - (Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani) Sandhills Marsh

- CEGL001685 Sporobolus airoides Southern Plains Wet Meadow

- CEGL001131 Symphoricarpos occidentalis Shrubland

- CEGL002010 Typha (latifolia, angustifolia) Western Marsh

Associated Animal Species

The Western Great Plains Floodplain system provides protected migration routes and abundant nesting, foraging and protected resources for many wildlife species. Mammal species include white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), opossum (Didelphis virginiana), muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), western harvest mouse (Reithrodontomys megalotis), and fox squirrel (Sciurus niger). Beavers (Castor canadensis) use plains cottonwood for food and for buildings dams and lodges. Cottonwoods stabilize streambanks and thereby provide fish with thermal cover, and protected undercut bank habitat. Plains cottonwood is the most important browse species for mule deer in the fall.

In Northeastern Colorado, plains cottonwood stands provide habitat for 82% of all of the bird species breeding in northeastern Colorado (Taylor 2001). Birds closely associated with cottonwoods on the Great Plains of Colorado include Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), Red-headed Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) which nest in cottonwood, Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), Lewis's Woodpecker (Melanerpes lewis) which breed predominantly in old decadent cottonwoods, Bullock's Oriole (Icterus bullockii), Yellow Warbler (Setophaga petechia), Western Kingbird (Tyrannus verticalis), Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), Eastern Kingbird (Tyrannus tyrannus), American Kestrel (Falco sparverius), and Blue Grosbeak (Passerina caerulea).

Abundant shelter, insects and warm temperatures make lowland floodplain and riparian ecosystems important habitat for reptiles and amphibians. Common reptiles and amphibians include tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum), plains leopard frog (Rana blairi), striped chorus frog (Pseudacris triseriata), Woodhouse's toad (Bufo woodhousii) and Great Plains toad (Bufo cognatus), painted and snapping turtle (Chrysemys picta and Chelydra serpentina), plains and red-sided garter snake (Thamnophis radix and T. sirtalis) and bullsnake (Pituophis melanoleucus) - many of which are restricted to the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains.

Dynamic Processes

Floodplains are highly dynamic. When a stream overflows its banks, natural levees form from the deposited sediments, water is supplied to the adjacent riparian wetlands and groundwater is recharged. When a stream erodes its channel, it moves laterally and downwards resulting in a meandering pattern. These processes of overbank flow, deposition and lateral migration are the most significant forces in the formation of a floodplain. Interactions between hydrologic and geomorphic processes result a mosaic of landforms including channels, floodplains, point bars and in-channel islands, which drive the spatial pattern and successional development of riparian vegetation. Floodplain woodlands and shrublands grow within a continually changing, dynamic alluvial environment due to the ebb and flow of the river, and are constantly being reset by flooding disturbance.

Regeneration and establishment of cottonwoods woodlands is dependent on flooding disturbance that occurs with appropriate timing and frequency, sufficient magnitude and duration, and slow regression in order to deposit wet, bare alluvium in full sun to enable germination and establishment. Additionally, seed dispersal must coincide with the timing of peak, snow-melt driven floods and sufficient soil moisture must be present throughout the late summer months when seedlings are vulnerable to water stress. Periodic flooding disturbance also maintains a diversity of age classes. Thus, functioning floodplain communities are a mosaic of various age classes containing early, mid- and late-seral associations. In fact, evidence form the South Platte Basin suggests that the floodplain naturally supported far fewer mature cottonwoods, as extreme floods prevented the establishment of large stands. Without flooding disturbance, floodplains become dominated by late-seral communities that are primarily upland species.

Management

In many floodplain and riparian systems, anthropogenic development has resulted in degradation or extirpation of floodplain wetland and prairie communities. Flow manipulation for flood control, urban water supplies and irrigation limits the flood events that cottonwoods need for seedling establishment and results in changes to plant and community composition. Where flow regulation has altered the timing of floods, cottonwood establishment may be constrained due to a lack of synchrony between seed dispersal and the availability of suitable substrates for germination.

Western Great Plains floodplains have often been subjected to heavy grazing and/or agriculture and can be heavily degraded. Invasion of exotic species is one consequence of the anthropogenic alteration of the river and surrounding land. Non-native plant species include saltcedar (Tamarix spp.) and Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) and less desirable or exotic grasses and forbs which displace native species. Non-native species do not provide the same essential ecosystem functions as do native species. For instance, saltcedar, unlike cottonwood, do not adequately stabilize stream banks nor do they provide appropriate nesting and foraging habitat for many native bird species. Further, saltcedar increase soil salinity thereby inhibiting revegetation by native species.

Global climate change has produced significant and changing trends in regional climate over the last few decades. Increased warming and changes in the water cycle are projected and the prospect of future droughts becoming more severe due to warming is a serious concern. In the mountains global climate change is altering the timing and magnitude of mountain snowmelt due to unprecedented springtime warming. Mountain snowmelt is the key driver of hydrology in this floodplain system. Because cottonwood seeds are only viable for 1 to 2 weeks after dispersal, appropriate timing of flooding flows are essential to seed germination and earlier snowmelt may result in dis-synchrony between flooding and seed dispersal. On the Great Plains, temperatures are projected to increase while precipitation is anticipated to increase in the north and decrease in the south. However, due to rising temperatures and increased evaporation, projected increases in precipitation are unlikely to be sufficient to offset decreasing soil moisture and water availability in the Great Plains. Current water use on the Great Plains is unsustainable as the aquifers continue to be tapped faster than the rate of recharge. Climate change projections will add more stress to overtaxed water sources impacting both agricultural and natural systems.

Colorado Version Authors

- Colorado Natural Heritage Program Staff: Dee Malone, Joanna Lemly, Cat Wiechmann

References

- Carsey, K., G. Kittel, K. Decker, D. Cooper, and D. Culver. 2003. Field guide to the wetland and riparian plant associations of Colorado. Prepared for the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, Denver, CO by the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Fort Collins, CO.

- Colorado Partners in Flight. 2000. Land Bird Conservation Plan. http://www.blm.gov/wildlife/plan/pl-co-10.pdf.

- Cooper, D. J., D. C. Andersen, and R. A. Chimner. 2003. Multiple pathways for woody plant establishment on floodplains at local to regional scales. Journal of Ecology 91:182-196.

- Gage, E. and D.J. Cooper. 2007. Historic Range of Variation Assessment for Wetland and Riparian Ecosystems, U.S. Forest Service, Region 2. Department of Forest, Rangeland and Watershed Stewardship, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.

- Kingery, H. E., editor. 1998. Colorado Breeding Bird Atlas. Colorado Bird Atlas Partnership and Colorado Division of Wildlife, Denver, CO. 636 pp.

- Kittel, G., E. Van Wie, M. Damm, R. Rondeau, S. Kettler, A. McMullen, and J. Sanderson. 1999. A Classification of Riparian Wetland Plant Associations of Colorado: A Users Guide to the Classification Project. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, College of Natural Resources, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Mutel, C.F. and J.C. Emerick. 1992. From grassland to glacier: The natural history of Colorado. Johnson Books, Boulder, Colorado.

- Pederson, G.T., S. T. Gray, C. A., Woodhouse, J. L. Betancourt, D. B. Fagre, J.S. Littell, E. Watson, B. H. Luckman, L. J. Graumlich. 2011. The Unusual Nature of Recent Snowpack Declines in the North American Cordillera. Science, 15 July 2011:Vol. 333 no. 6040. Pp.332-335.

- Rondeau, R.J. 2001. Ecological system viability specifications for Southern Rocky Mountain ecoregion. First Edition. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO. 181 pp.

- Windell, J.T. 1992. Stream, Riparian and Wetland Ecology. University of Colorado, Boulder, CO. 222 pp.

- Karl, T.R., J.M. Melillo, and T.C. Peterson (eds.). 2009. Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY.