Western Great Plains Shortgrass Prairie

Click link below for details.

General Description

Shortgrass prairie is characteristic of the warm, dry southwestern portion of the Great Plains, lying to the east of the Rocky Mountains, and ranging from the Nebraska Panhandle south into Texas and New Mexico. The northern extent of this type represents the transition to cooler, more mesic mixed-grass types, generally occuring in southeastern Wyoming and southwestern Nebraska, although occasional shortgrass stands may be found further north. In Colorado, the shortgrass prairie system is found at elevations from about 1,110 m (3,650 ft) at the eastern border, to around 1,830 m (6,000 ft) near the mountain front, where it may intergrade with foothill and piedmont grasslands. The larger intact tracts are in southeastern Colorado. Prior to settlement, the shortgrass prairie was a generally treeless landscape characterized by blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) and buffalo grass (Buchloe dactyloides). In much of its range, shortgrass prairie forms the matrix vegetation with blue grama dominant. Other grasses include three-awn (Aristida purpurea), side-oats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), hairy grama (Bouteloua hirsuta),needle-and-thread (Hesperostipa comata), June grass (Koeleria macrantha), western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), James' galleta (Pleuraphis jamesii), alkali sacaton (Sporobolus airoides), and sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus). Local inclusions of mesic or sandy soils may support taller grass species including sand bluestem (Andropogon hallii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), and prairie sandreed (Calamovilfa longifolia), as well as scattered shrub species including sandsage (Artemisia filifolia), prairie sagewort (Artemisia frigida), fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens), tree cholla (Cylindropuntia imbricata), spreading buckwheat (Eriogonum effusum), snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae), pale wolfberry (Lycium pallidum), and soapweed yucca (Yucca glauca) may also be present. One-seed juniper (Juniperus monosperma) and occasional pinyon pine (Pinus edulis) trees are often present on shale breaks within the shortgrass prairie matrix.

Diagnostic Characteristics

This system is characterized by extensive areas dominated by blue grama, and formerly, by buffalo grass. These low-stature perennial grasses are a unifying and persistent factor in shortgrass prairie of Colorado's eastern plains. Variation in the prevalence and composition of forb species, and patchy distribution of occasional trees, shrubs, and mesic swales gives these grasslands a constantly changing aspect both seasonally, and between years.

Similar Systems

Range

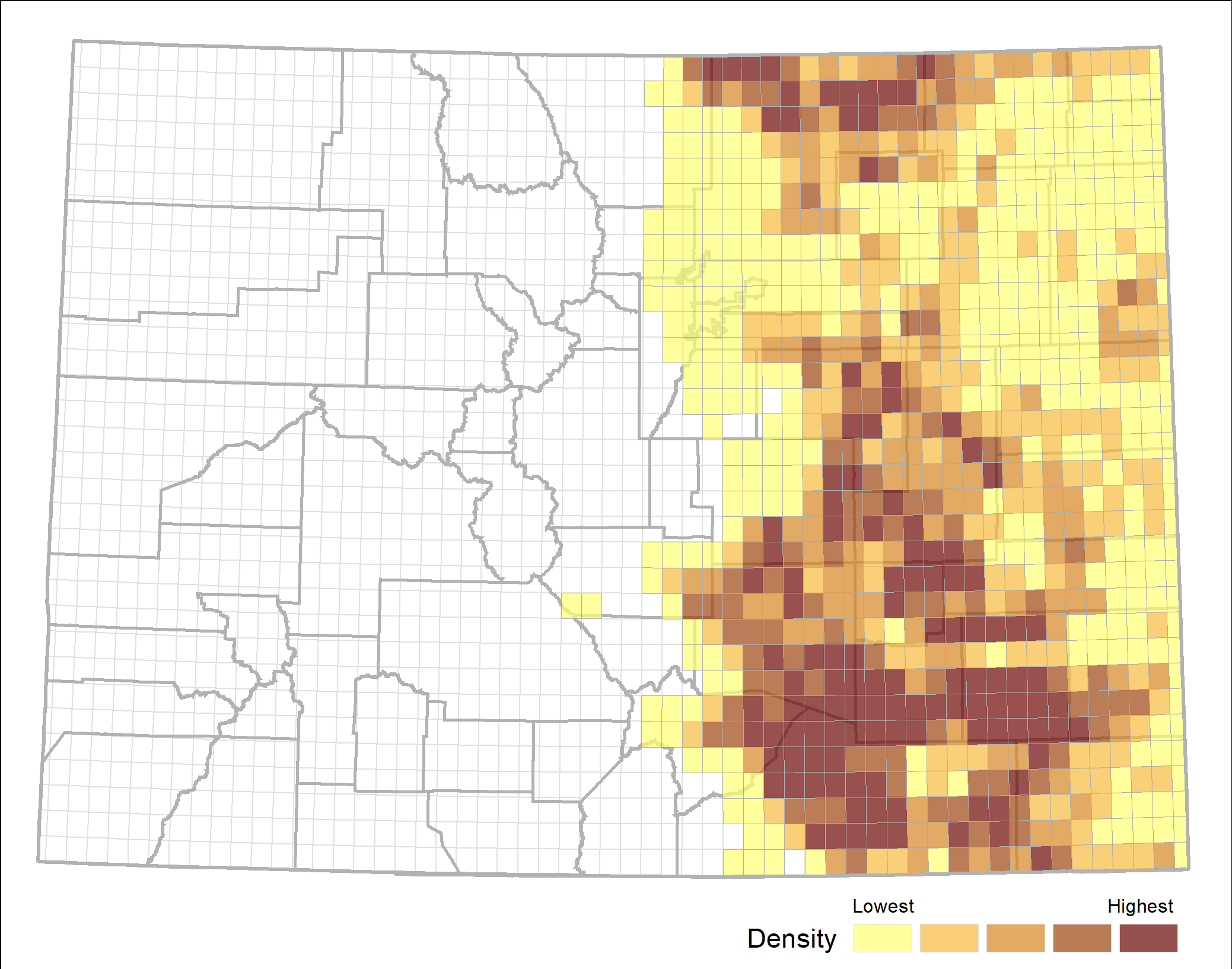

This system is found in the southwestern portion of the Great Plains, lying to the east of the Rocky Mountains, and ranging from southern Wyoming and the Nebraska Panhandle south into Texas and New Mexico. In Colorado, the shortgrass prairie system is found at elevations from about 1,110 m (3,650 ft) at the eastern border, to around 1,830 m (6,000 ft) near the mountain front. Colorado's largest intact tracts are in the southeastern portion of the state.

Ecological System Distribution

Spatial Pattern

Western Great Plains Shortgrass Prairie is a matrix forming system.

Environment

The climate of the shortgrass prairie is characterized by large seasonal contrasts, as well as interannual and longer term variability. The shortgrass prairie region is classified as a semi-arid. Annual precipitation is generally less than 50 cm (20 in), and soils are periodically moist only in a shallow top layer typically less than half a meter (1-2 feet) deep.

Winters in the shortgrass prairie can be mild and dry when Pacific air masses are blocked by the Rocky Mountains under zonal flow conditions, or cold and snowy under meridional flow patterns that bring arctic air or upslope snow. Spring is transitional with warming conditions and lingering arctic air and possible heavy snow. Spring warming brings thermal instability and atmospheric mixing producing windy conditions, and thunderstorms become common. Tornados and slow-moving storms producing heavy precipitation may also occur. In summer a dryline separating humid Gulf air from dry desert southwest air forms in the western plains, and thunderstorms often form along this boundary. Summer thunderstorms can produce locally heavy precipitation. In late summer, the North American monsoon can bring moisture from the southwest. Typical autumn weather in the shortgrass region is relatively fair and dry, with periodic cool, wet weather and the possibility of early snow.

These grasslands occur primarily on flat to rolling uplands with loamy, ustic (dry, but usually with adequate moisture during growing season) soils ranging from sandy to clayey, at elevations generally below 1,830 m (6,000 ft). Organic matter accumulation in shortgrass prairie soils is primarily confined to the upper 20 cm. The action of a freeze-thaw cycle on these grassland soils increases their vulnerability to wind erosion in late winter and spring.

Vegetation

Shortgrass prairie is characterized by short-stature grasses, along with scattered mid-height grasses, a variety of perennial and annual forbs, and patches of shrubs or subshrubs. Prior to settlement, the shortgrass prairie was a generally treeless landscape characterized by blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis) and buffalo grass (Buchloe dactyloides). In much of its range, shortgrass prairie forms the matrix vegetation with blue grama dominant. Other grasses include three-awn (Aristida purpurea), side-oats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), hairy grama (Bouteloua hirsuta),needle-and-thread (Hesperostipa comata), June grass (Koeleria macrantha), western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii), James' galleta (Pleuraphis jamesii), alkali sacaton (Sporobolus airoides), and sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus). Local inclusions of mesic or sandy soils may support taller grass species including sand bluestem (Andropogon hallii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans), and prairie sandreed (Calamovilfa longifolia), as well as scattered shrub species including sandsage (Artemisia filifolia), prairie sagewort (Artemisia frigida), fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens), tree cholla (Cylindropuntia imbricata), spreading buckwheat (Eriogonum effusum), snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae), pale wolfberry (Lycium pallidum), and soapweed yucca (Yucca glauca) may also be present. One-seed juniper (Juniperus monosperma) and occasional pinyon pine (Pinus edulis) trees are often present on shale breaks within the shortgrass prairie matrix.

- CEGL005800 Aristida purpurea Grassland

- CEGL001749 Bouteloua eriopoda - Bouteloua hirsuta Grassland

- CEGL001754 Bouteloua gracilis - Bouteloua curtipendula Grassland

- CEGL001756 Bouteloua gracilis - Bouteloua dactyloides Grassland

- CEGL001755 Bouteloua gracilis - Bouteloua hirsuta Grassland

- CEGL005389 Bouteloua gracilis - Muhlenbergia torreyi - Aristida purpurea Grassland

- CEGL001759 Bouteloua gracilis - Pleuraphis jamesii Grassland

- CEGL001760 Bouteloua gracilis Grassland

- CEGL004588 Cylindropuntia imbricata Ruderal Shrubland

- CEGL001685 Sporobolus airoides Southern Plains Wet Meadow

Associated Animal Species

Prior to European settlement, the shortgrass prairie supported abundant herds of bison (Bison bison), pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), and grassland birds, together with their predators. This system remains important to a number of bird and mammal species. Birds characteristic of the shortgrass prairie include Western Meadolark (Sturnella neglecta), Horned Lark (Eremophila alpestris), Lark Bunting (Calamospiza melanocorys), Lark Sparrow (Chondestes grammacus), Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum), Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura), Cassin's Sparrow (Peucaea cassinii), Killdeeer (Charadrius vociferous), Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus), Mountain Plover (Charadrius montanus), Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor), Burrowing Owl (Athene cunicularia), McCown's Longspur ( Rhynchophanes mccownii), Chestnut-collared Longspur (Calcarius ornatus), Swainson's Hawk (Buteo swainsoni), Ferruginous Hawk (Buteo regalis), and Prairie Falcon (Falco mexicanus). Typical mammals include coyote (Canis latrans), badger (Taxidea taxus), swift fox (Vulpes velox), white-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus townsendii), desert cottontail (Sylvilagus audubonii), black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), and smaller rodents. Amphibians include green toad (Anaxyrus debilis) and Couch's spadefoot toad (Scaphiopus couchii); reptiles include Hernandez's short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma hernandesi), many-lined skink (Plestiodon multivirgatus), coachwhip snake (Coluber flagellum), glossy snake (Arizona elegans), massasauaga (Sistrurus catenatus), and prairie rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis).

Dynamic Processes

Large-scale processes such as climate, fire and grazing influence this system.

Drought in the shortgrass prairie region can occur during any season, and generally has its greatest impact during the growing season, when most annual precipitation occurs. Although severe droughts are often accompanied by high temperatures, paleoclimatic data indicate that severe drought has also occurred with cold temperatures, resulting in different types of stress on ecosystems. Although causes of widespread and lengthy drought are not compeletly understood, they are likely due in part to large-scale, low-frequency ocean and atmospheric circulation patterns.

Although fire is of somewhat lesser importance in shortgrass prairie compared to other prairie types, it is still a significant source of disturbance. The xeric climate of the shortgrass reduces overall fuel loads, but also dries vegetation sufficiently for it to become flammable. The generally open, rolling plains and often windy conditions in the shortgrass prairie facilitate the spread of fire when fuel loads are sufficient. With growing points below or near the surface, grasses are well protected from heat of most fires, and able to resprout, and regain dominance.

Shortgrass prairie developed in the presence of large grazers, especially bison, and grazing remaing the primary land use for most remaining shortgrass tracts. The overall species composition of shortgrass is influenced by grazing. Blue grama is considered tolerant of grazing, generally increasing under grazing except at the highest intensity, and buffalo grass is highly tolerant of disturbance, including heavy grazing. There is some evidence that the dispersal of both species is facilitated by large herbivore grazing. Where bluffs, breaks, or swales provide refuge from grazing, plant species that are rare in adjacent grazed areas become more common.

Management

Extensive portions of this ecosystem have been converted to cropland. Conversion to cropland replaces native shortgrass prairie with row crops, hay fields, and similar vegetation, with a consequent loss or fragmentation of habitat for native wildlife. Ground-water pumping of the Ogallala aquifer has already lead to aquifer drops of more than 15 m in parts of the central and southern Great Plains. Agricultural use of the remaining intact shortgrass prairie is dominated by domestic livestock grazing.

Effects of livestock grazing in shortgrass are not limited to changes in species composition, but can also impact ecosystem structure and function by changing litter accumulation rates, increasing soil compaction or erosion, decreasing moisture infiltration and removing biological soil crusts. Ancillary effects from livestock ranching in the shortgrass prarie include the disruption of the historic foodweb through removal of "problem animals (e.g. wolves, bears, coyotes, prairie dogs, raptors, snakes, etc.) or biomass removal that eliminates resources for scavengers and decomposers. Fencing and roads associated with ranching have greatly fragmented the shortgrass prairie habitat, and allowed the invasion of exotic species.

Warmer summer nighttime low temperatures and/or extended periods of drought are likely to change the balance of warm- and cool-season grasses, and, if fire frequency remains low, allow the establishment of woody species, with the potential for conversion to a more arid grassland type or savanna. Shortgrass prairie is vulnerabe to the effects of climate change by mid-century. A primary contributing factor is the location of these grasslands on the eastern plains of Colorado, where the greatest levels of exposure for all temperature variables occur. Warmer and drier conditions would be likely to reduce soil water availability and otherwise have detrimental effects on ecosystem processes, while warmer and wetter conditions could be favorable. Furthermore, changing climate may lead to a shift in the relative abundance and dominance of shortgrass prairie species, giving rise to novel plant communities. Because woody plants are more responsive to elevated CO2, and may have tap roots capable of reaching deep soil water, an increase of shrubby species (e.g., cholla, yucca, snakeweed, sandsage), or invasive exotic species, especially in areas that are disturbed (for instance, by heavy grazing) may also result.

References

- Anderson, R.C. 1990. The historic role of fire in the North American Grassland. Chapter 2 in Collins, S.L. and L.L. Wallace, eds., Fire in North American Tallgrass Prairies, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

- Axelrod, D.I. 1985. Rise of the grassland biome, central North America. Botanical Review 51:163-201

- Bock, C. E., and J. H. Bock. 1988. Grassland birds in southeastern Arizona: impacts of fire, grazing, and alien vegetation. ICBP Technical Publication No. 7:43-58.

- Carpenter, J.R. 1940. The grassland biome. Ecological Monographs 10:617-684.

- Coffin, D.P., W.K. Lauenroth, and I.C. Burke. 1996. Recovery of vegetation in a semiarid grassland 53 years after disturbance. Ecological Applications 6:538-55.

- Dickinson, C.E. and J.L. Dodd. 1976. Phenological pattern in the shortgrass prairie. American Midland Naturalist 96:367-378.

- Ellison, L. 1960. Influence of grazing on plant succession of rangelands. The Botanical Review 26:1-78.

- Fleischner, T.L. 1994. Ecological costs of livestock grazing in western North America. Conservation Biology 8:629-644.

- Ford, P.L. and G.R. McPherson. 1997. Ecology of fire in shortgrass prairie of the southern Great Plains. Pages 20-39 in Ecosystem Disturbance and Wildlife Conservation in Western Grasslands. General Technical Report RM-285, USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Hart, R.H. 2008. Land-use history on the shortgrass steppe. Chapter 4 in Lauenroth, W.K. and I.C. Burke (eds.) 2008. Ecology of the Shortgrass Steppe: a long-term perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Kelly, E.F., C.M. Yonker, S.W. Blecker, and C.G. Olson. 2008. Soil development and distribution in the shortgrass steppe ecosystem. Chapter 3 in Lauenroth, W.K. and I.C. Burke (eds.) Ecology of the Shortgrass Steppe: a long-term perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Lauenroth, W.K. and O.E. Sala. 1992. Long-term forage production of North American shortgrass steppe. Ecological Applications 2:397-403.

- Pielke Sr., R.A. and N.J. Doesken. 2008. Climate of the shortgrass steppe. Chapter 2 in Lauenroth, W.K. and I.C. Burke (eds.) 2008. Ecology of the Shortgrass Steppe: a long-term perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Polley, H.W., D.D. Briske, J.A. Morgan, K. Wolter, D.W. Bailey, and J.R. Brown. 2013. Climate change and North American rangelands: trends, projections, and implications. Rangeland Ecology & Management 66:493-511.

- Rondeau, R.J., K.T. Pearson, and S. Kelso. 2013. Vegetation response in a Colorado grassland-shrub community to extreme drought: 1999-2010. American Midland Naturalist 170:14-25.

- Samson, F. B. and F. L. Knopf. 1996. Prairie conservation: Preserving North America's most endangered ecosystem. Island Press, Covelo, California.

- Scheintaub, M.R., J.D. Derner, E.F. Kelly, and A.K. Knapp. 2009. Response of the shortgrass steppe plant community to fire. Journal of Arid Environments 73:1136-1143.

- Shantz, H.L. 1923. The natural vegetation of the Great Plains region. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 13:81-107.

- Sims, P.L., and P.G. Risser. 2000. Grasslands. Chapter 9 in: Barbour, M.G., and W.D. Billings, eds., North American Terrestrial Vegetation, Second Edition. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Wells, P.V. 1970. Postglacial vegetational history of the Great Plains. Science 167:1574-1582.

- Morgan, J.A., D.G. Milchunas, D.R. LeCain, M. West, and A.R. Mosier. 2007. Carbon dioxide enrichment alters plant community structure and accelerates shrub growth in the shortgrass steppe. PNAS 104:14724-14729.