Introduction

This summer, I had the wonderful opportunity to gain real-world conservation biology work through CNHP’s Siegele Conservation Science Internship. Throughout the summer, I spent the majority of my time split between 2 main projects: Ana Davidson’s Prairie Dog Plague Study and the Preble’s Meadow Jumping Mouse project led by Terutaka Funabashi. After an introductory week in the office, meeting all the interns and learning about our respective projects, and a week of in-field training at Rifle Ranch, I was sent off on my summer adventures.

Prairie Dog Study.

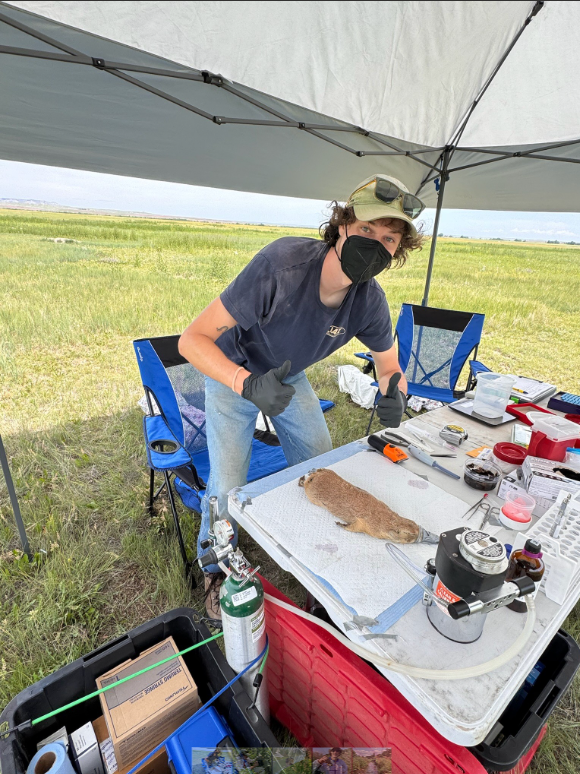

Days on this project began well before sunrise; that tends to be the nature of things when you’re working with small mammals. 4 AM, we would be up and ready to bait the traps, pouring a mix of horse feed, oats, and carrots into the traps under the light of our headlamps. Once all the traps had been baited and set (ideally as the sun was rising, which led to some awesome sunrises over the plains) we would head back to the basecamp and try to catch two extra hours of sleep. Around 8 AM, it was time to head back out and check on the traps. Under the shade of our field tent, you could see prairie dogs scurrying about, some minding their business, some inching farther and farther into the traps. Throughout the morning to midday, we spied on the prairie dogs, wishing them into the traps. The real excitement of the day always began when the first couple of prairie dogs got caught.

There is nothing quite like holding a passed-out prairie dog in your hands, at least nothing I’ve ever done matches the experience. The first step in our process was getting the prairie dogs safely anesthetized. Turns out controlling an upset prairie dog is not a particularly easy task. Using as much finesse as possible, we would guide each prairie dog into a cone-shaped canvas bag, gently place the oxygen mask over their little nose, and turn up the anesthesia. One of my favorite parts of the process was making sure the prairie dog was properly anesthetized, done by gently pulling on its leg for a reaction. Once fully under, we would get to work scraping off and collecting all of the fleas. I am proud to say that I personally helped scrape 47 fleas off a particularly infested prairie dog. Once fleas were collected, we would take a snip of the ear for a genetic sample, draw blood, and take various measurements, including length and weight. Finally, each animal was given a PIT tag and semi-permanent marking. Learning all of these aspects and techniques of wildlife data collection was both enthralling every time as well as incredibly educational.

Throughout my time on this project, I got to experience some truly incredible landscapes. I have a much greater appreciation for the beauty of the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. One of our hitches was as far out as Nebraska, a new state for me and one I now desperately want to go back to. One thing constant throughout all of these locations, rattlesnakes, and lots of them, I can still hear some of them rattling.

Prebles Meadow Jumping Mouse.

Another project with an early start, but who can complain when you wake up with the possibility of getting to work up close with one of Colorado’s rarest and cutest rodents. Working on the Air Force Academy outside of Colorado Springs, which has a surprisingly ecologically intact watershed, we spent our mornings on this project opening up traps hidden in the thick willows and grasses next to streams. Unlike the open tomahawk traps we used in the prairie dog traps, the Sherman traps used on this project were fully enclosed, making opening each one feel like opening a present on Christmas morning. Vols, Shrews, Woodrats, and Deermice were all common finds in the traps, but none brought the same level of excitement as a Jumping Mouse. When a jumping mouse was caught, it would be placed in a bag to be weighed. Then we would scruff the animal (a process that took some learning for me) to sex and mark each individual. While every jumping mouse captured was an unforgettable experience, I managed to form a bond with a particular animal, Carmichael the jumping mouse. Found on a cold and rainy morning in one of our traps, Carmichael was lethargic and too cold to release, so we placed him in a wool bag with some extra food and took him back to the car to heat him up. Driving around with a little mouse sat on my lap is an experience I will never forget. Carmichael, quickly rewarmed and was safely released, giving a great ending to an awesome morning. After every trap had been checked, we completed vegetation surveys at each site. While learning how to collect habitat quality data was something I am grateful for, plus everyone should learn how to bushwak through dese willows at somepoint in their life.

Working to protect a native and endangered species was an honor and incredibly rewarding. I was the only intern during my time on this project and worked solely with Funa, the project lead. Funa was an amazing boss and mentor, constantly giving me helpful advice and teaching me about the behind-the-scenes of wildlife studies. This project gave me an appreciation for the conservation work being done in developed areas. The Air Force Academy is far from pristine wilderness, but the Fish and Wildlife Service, partners on this project, have done a great job of doing the most with what’s available, creating high-quality quality valuable habitat. I got to see bears, elk, deer, coyotes, and release a beaver, all just 10 minutes outside of a major city.

Conclusion

My summer as a Siegele intern was filled with new experiences and fond memories. I learned important wildlife handling and sampling skills and got to practice many of the field collection methods I’ve learned about in class. I learned so much from my coworkers and project leads, making connections I hope last long into the future.