I’ve always been connected to nature. It is hard for me to put this feeling into words . . . there is something about the crisp Colorado air, filled with the smells of spruce and fir, vanilla butterscotch from ponderosa pine, that calms my nerves and creates peace of mind. Growing up along the Colorado Front Range, I spent a lot of time outside, usually at a cabin in Evergreen running barefoot across fallen pine needles or wading through icy streams, not knowing about complex issues of water rights or forest management. The world was just there for me to explore, experience, and learn from.

Banding Western Meadowlark

June 9, 2023: 3:30 a.m.

The sound of my alarm drags me from groggy sleep. Inherently, I am not a morning person. But the birds are. A little begrudgingly, I crawl from underneath the warmth of my sheets to take a quick shower before grabbing a muffin and a Yerba Mate before heading out to pick up River, another intern who will be joining me to band Western Meadowlarks with the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies (BCR).

I do not typically work with wildlife. Consequently, our drive to Soapstone Prairie Natual Area was for me, a nervous one. We arrived a little early, so I had the chance to take a few deep breaths and ground myself before Matt Webb, and avian ecologist at BCR, arrived with his team. Soon, their headlights were illuminating the otherwise dark landscape and we quickly introduced ourselves before driving to our first site.

The sun was just peeking over the eastern horizon as we arrived, lighting up the awns of needle and thread grasses, turning the sky from deep indigo to a composite of warm yellows, glowing oranges, and my favorite: soft pink. With only a few wispy clouds hanging over the prairie, it was a beautiful sunrise. And we could hear him — the whistling and warbling of a male western meadowlark singing across the landscape. The team quickly unloaded long poles and mist nets, stretching them out across a fence line before placing a Bluetooth speaker and decoy bird, painted with the distinct yellow belly and black “V,” in the net.

Almost immediately after we all crouched down behind the sparse rabbitbrush, making ourselves small and inconspicuous, the bird was in the net. Western meadowlarks are a highly territorial species, and the decoy song playing over the speaker encouraged the male to find it’s singer and defend his territory. We all jumped up, ran to the net, and Matt carefully untangled the bird’s wings and legs from the fine net, hushing softly. Efficiently, the team took him back to the open trunk of their car, where they weighed and measured him before inspecting his wing feathers. After determining that he was an appropriate size, they quickly had two metal bands wrapped around each leg and placed a Lotek tag on his back. This device helps BCR track migratory birds and is essentially a solar powered GPS that is smaller than the pads of my thumb and is worn by the bird like a backpack.

This project aims to help scientists understand how western meadowlarks utilize their range, which will be critical in implementing protections and conservation efforts. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, grassland bird populations have declined 53% since the 1960’s, and BCR is working hard with their partners to fill in the gaps of knowledge surrounding migratory bird patterns. This was an incredible opportunity to work outside of my comfort zone, learn something new, and contribute to a very interesting conservation effort.

Fen Mapping

July 5-11 and 18-25, 2023 | Grand Teton National Park As I’ve grown older, it has become increasingly difficult to remember the joys of nature. As a restoration ecologist I look at disturbances and think of how to ‘fix’ them, all within the legalities of U.S. resource management, and not always for the benefit of ecosystems. Looking at a stream filled with non-native fish, walled off with boulders to maintain flow that guides it to dams and reservoirs, preventing it from slowing down, from meandering in the way rivers are supposed to wander. The lead scientist calls this a wetland restoration. I see no wet land. Upland sedges populate the surrounding ground, a couple willows sprouting beyond the channel’s walls. There is no squish, no bounce to the soil. It is as hard as the rocks that were mined from the stream.

As I’ve grown older, it has become increasingly difficult to remember the joys of nature. As a restoration ecologist I look at disturbances and think of how to ‘fix’ them, all within the legalities of U.S. resource management, and not always for the benefit of ecosystems. Looking at a stream filled with non-native fish, walled off with boulders to maintain flow that guides it to dams and reservoirs, preventing it from slowing down, from meandering in the way rivers are supposed to wander. The lead scientist calls this a wetland restoration. I see no wet land. Upland sedges populate the surrounding ground, a couple willows sprouting beyond the channel’s walls. There is no squish, no bounce to the soil. It is as hard as the rocks that were mined from the stream.

This was hard for me to see. It is not my intention, nor my purpose, to insult the incredible work that was done at this site. But it was still hard. Partially because I had the opportunity to stand in fen wetlands, balanced on floating mats looking out at the incredible species diversity of these ecosystems. Sometimes what is lost may never be found again.

Fens are a groundwater fed wetland that have at least 40cm of organic soil, also known as histosols or peat. This process takes thousands of years and is a result of saturated soils slowing the decomposition rate of organic matter, ultimately being an incredibly efficient carbon sink that is also a unique environment for plants to grow.

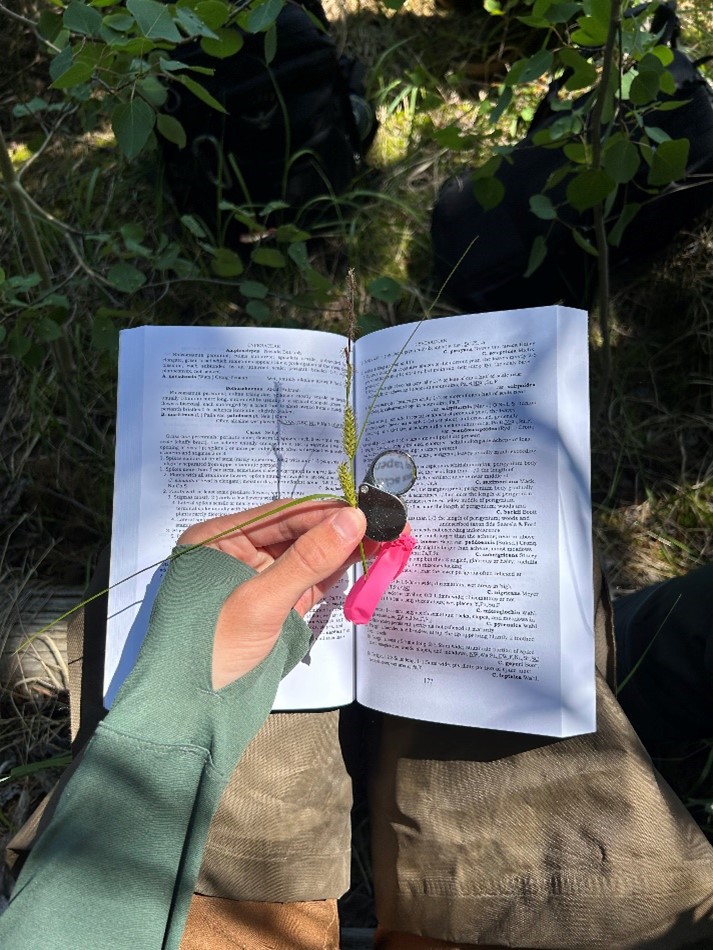

It was fascinating digging into the soil, ankles hidden by pooled groundwater. To see acres of Carex buxbaumii, a rare sedge in the state of Wyoming. To hold an English sundew (Drosera anglica), a rare carnivorous plant in Wyoming. This project aimed to provide the accurate locations of fens in Grand Teten National Park, so as they develop further infrastructure, they know which areas should be protected. I truly felt like I was contributing to something important on this project, helping these unique wetlands be recognized. They are hotspots of biodiversity, near impossible to restore, and hold incredible amounts of carbon. And yet we still drain them (outside of the park) for agriculture and urban development. I am so grateful for this opportunity, which gave mee a personal connection to these ecosystems so that I can be a better voice for their protections.

Conclusion

Although I am not a religious person myself, there is a quote from Genesis 3:19 that says, “for you are dust and to dust you shall return.” This phrase resonates with me for many reasons, one of which being that it iterates this concept of connectivity — that humanity is of the earth. We may build cities and skyscrapers, steel concrete environments that long ago forgot what once grew there. We can achieve the incredible by sending people to space –landing on the moon — which may not be another planet but is undeniably not Earth. We can create virtual realities via great strides in technology. All unquestionably good things . . . but there will be no reality more real than this one. Earth. Try as hard as we might, one day we will return to it. The elements that make up our human anatomy will return the soil and provide resources for the next round of life. We are not separate from our responsibilities in trophic systems. It can be hard to remember, in our cities and virtual realities, but one day, we will return to dust.

I think overall, this internship developed my connection to the world and those who work to protect it. I met some truly inspiration people and will be forever grateful for the lessons they shared. Thank you.