by the ESS 440 Anthropogenic Disturbance Team

Throughout the spring 2017 semester at Colorado State, seniors in the ecosystem science program have been working through their senior project with the help of a local Colorado agency or organization. This blogpost is an overview of one of the team’s collaboration with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program. For more information on the team and an overview of this project, please see our previous blog post, found here.

The Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) has worked in Colorado since 1979, cataloguing information about the rare and endangered species that exist within the state. One aspect of their work has been the creation of potential conservation areas (PCAs) in Colorado. A PCA is an area created to denote some level of biodiversity significance. CNHP has identified these areas in the hopes of protecting the plants and animals that reside within it. The main objective of the following project is to build upon CNHP’s work in order to better understand the level at which potential conservation areas (PCAs) in Colorado have been disturbed by human activities.

|

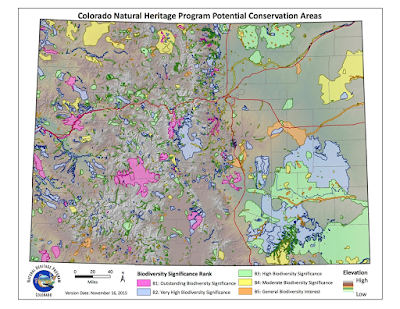

| Location and rank of Colorado’s potential conservation areas (PCAs) |

The map above gives the location and rank of each PCA that has been identified by CNHP in Colorado. An area shown in pink, given the rank of B1, surrounds species that are deemed to have outstanding levels of biodiversity significance. These are highly important areas for conservation and contain Colorado’s rarest or most imperiled species. Orange sites given a rank of B5 on the other hand, hold species of more general biodiversity significance, likely containing communities that are healthy and relatively abundant in the state.

This map helps focus conservation efforts by ranking areas of biodiversity significance that may be currently unprotected. Areas given a higher ranking such as B1 or B2, are higher priority for conservation. However, to add another layer of information to this idea, our team wanted to find how much anthropogenic, or human, disturbance has taken place in each of these areas.

The first thing the team did was use the location and rank information from each of Colorado’s PCAs and combine it with a landscape disturbance index (LDI) dataset. The LDI dataset contains information about a type of disturbance that has been created and that disturbance type’s severity level.

|

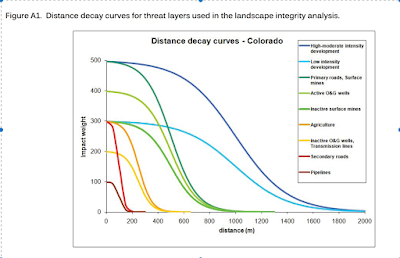

| Distance decay curves used to determine the disturbance range of each anthropogenic activity (reproduced from Rondeau et al. 2011) |

Above, you can see the distance decay curves that were used as part of the LDI dataset. Each curve is associated with one of the nine types of mappable anthropogenic disturbance. The curve assigns an impact weight, the amount of disturbance created, over a distance to each type of disturbance activity. Some activities have a further reaching effects than others. For example, low intensity urban development has an initial impact weight of 300, however it still creates some level of disturbance up to 2000 meters away. Agriculture on the other hand, also carries an initial impact weight of 300, but its furthest reaching effects end at 500 meters.

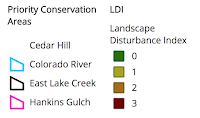

Anthropogenic disturbance in Colorado displayed on a color scale ranging from green to red (CNHP 2016). Green denotes undisturbed areas. Red denotes highly disturbed areas. The PCAs that were the focus of this study are highlighted in various colors.

Anthropogenic disturbance in Colorado displayed on a color scale ranging from green to red (CNHP 2016). Green denotes undisturbed areas. Red denotes highly disturbed areas. The PCAs that were the focus of this study are highlighted in various colors.

In general, areas along the Front Range and the eastern plains of Colorado have experienced the greatest amounts of anthropogenic disturbance. This is due to the high population density along the Front Range and eastern Colorado’s agricultural activity. From the Rocky Mountains westward, there are much lower level of disturbance in the state. A major factor of this is the ruggedness of the terrain. Mountain areas are less accessible to people and have lower population density. Many mountain areas may also currently have some level of protection surrounding them, such as a state or national forest.

Having this new information about the level of disturbance an area experiences, allows conservation efforts to be balanced. While a B1 area may have greater biodiversity significance than a B2 area, it is possible that the B2 area is experiencing a greater amount of anthropogenic disturbance and therefore may be considered a higher priority for conservation.

Through our analysis, we identified the most and least disturbed B1 PCAs in the state. In the above map, you can see an area in western Colorado highlighted in blue. This area is the Colorado River PCA. It is a B1 PCA and home to the endangered Colorado pikeminnow, humpback chub, and razorback sucker. It is the most disturbed B1 PCA in Colorado primarily due to its proximity to the I-70 urban corridor. Not addressed in the LDI are additional significant impacts, such as the large amount of agricultural water diversion used for irrigation. Water diversions use dams and canals to draw water out of the river.

In contrast, Colorado’s Hankins Gulch, located in central Colorado and shown in pink, is the least disturbed B1 PCA in the state. The area has a minimum elevation of 8,305 ft., meaning the mountainous terrain puts this area out of reach for many activities and land uses. Additionally, motorized vehicle usage is also prohibited within the area, further reducing accessibility to the area for most people. Hankins Gulch receives its B1 PCA status because it is home to the critically imperiled budding monkeyflower (Mimulus gemmiparus).

While this was just one example of the scope at which human disturbance can affect a PCA, identifying areas in Colorado that are heavily disturbed by humans is an important step in prioritizing conservation efforts in order to most effectively protect Colorado’s biodiversity. For more information, please follow this link to an interactive Story Map created about the project.

Special thanks to Michelle Fink and David Anderson of CNHP for their contributions and guidance with this project.

—

CNHP. 2016. Landscape Disturbance Index Layer for Colorado. Edition 12_2016. Raster digital data. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.

Rondeau, R., K. Decker, J. Handwerk, J. Siemers, L. Grunau, and C. Pague. 2011. The state of Colorado’s biodiversity 2011. Prepared for The Nature Conservancy. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.