By Hannah Varani, CNHP Wetland Ecology Field Technician

For the past two summers, I’ve been working with CNHP Wetland Ecologist Joanna Lemly on a project known in our office as REMAP. Contrary to what you might think from the name, this is not one of our wetland mapping projects. It is a collaborative project between the Natural Heritage Programs of Colorado, Montana and Wyoming that is funded through EPA’s Regional Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Program (hence, REMAP). The goals of the project are to 1) develop a standardized approach to assessing wetland condition across the Rocky Mountains and 2) establish baseline data of “un-impacted” wetlands or wetlands as they naturally occur in the absence of human impact. The Natural Heritage Programs and EPA will use this data to further refine field protocols for future wetland assessment projects. They will also use this data to compare with data gathered on “impacted” wetlands.

Now that’s a fine first paragraph don’t you think? So much information packed into each short(ish) sentence. It took me just a few minutes and some finger flexing to condense the work of so many people and countless hours into a handful of words. This parallels my experiences with the project. Let’s take, for example, this past summer.

After many months of planning, my field partner, Kat Sever, and I were ready to start gathering field data in sites all over Colorado. On paper, our days looked like they would be similar to each other. They read like this: drive to a site, sample the site, camp, then drive to the next site, and repeat. In retrospect, you could say that this is a concise summarization of the reality. Yes, this is what we did… but to me, like the first paragraph, it feels so glossy. Let me elucidate the steps.

Driving to the site

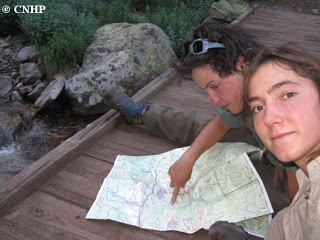

First, this included packing the car. All summer, we drove a rented, white Ford explorer with Utah plates. We nick-named her “Starlene” and imagined her as a rhinestone cowgirl type: luxurious with working air conditioning but rough enough for the roads we were going to be accessing… barely. Half of the back space was already claimed by necessary field gear, books and maps. Over the course of the summer, Kat and I became adept at jigsawing all our food, camping gear, day packs, personal items, and any duplicate items necessary for the two weeks (or longer) we planned to be out. We had a system of organization that would completely deteriorate into complete bedlam by the second week nearly every time. Inevitably stopping along the way to pick up forgotten items in towns that had stores, we would begin the 2-8 hour drive to our site. Struggling with the map and directions typically only became a focused activity as we got closer to each spot. Have you ever noticed that while many dirt roads are signed, their signs often don’t match the labels on your map? Have you ever noticed that there are roads where there is no business for a road to be and is that a pothole there in the middle of the road or just an early grave?!

Eventually, Starlene would get parked and Kat and I would either set up camp or get ready to continue on to the site. In most cases it turns out that “un-impacted” sites, like the ones we were looking for, tended to occur in hard to access areas (surprise!). But even miles into the backcountry, we would still find evidence that people had been there before us.

This meant that we had to backpack into the majority of them. It also meant most of them included some travel off trail. Picture burned areas with downed logs in every direction, picture rows of sheer cliffs directly in the path, picture the Rocky Mountains in all their steep steepness. Reaching our final destination meant sweating. Profusely. Picture blisters and back sprains.

This is us: after just a few miles we feel as if we’ve been beaten and are ready to stop but we’re just not quite there yet. By this point we had a mantra: “just a little further, a few more miles to go.” The expression on our faces: pure enthusiasm.

Sampling the site

Inevitably we would arrive at the spot where we would gather the data. I think a picture is the only way to really capture the labor spent maneuvering around our 1/2 hectare sample sites.

Yeah, I’ll need to forge a path through this to do what I signed up for.

This is what that looks like: nobody said it would be pretty.

It would be exaggerating to say that every site was covered in shrubbery like this one, some were much more open.

Regardless, by the end of the summer Kat and I were pleasantly surprised that neither of us had broken an ankle. But I came to the following conclusions: invisible sinkholes are a common hazard in wetland work, as are wet shoes and stinky feet (especially in small, enclosed, shared spaces such as tents).

Alpine thunder and hailstorms are kind of fun, but also definitely a hazard. Don’t forget the Rite in the Rain® paper.

Camping

Data collected, shoes soaked, we were now prepared to spend our “ample” free time camping (and pressing plants, and identifying anything we had the stamina for). What can I say about camping that hasn’t been said before? Especially in backpacking situations, it seems that most of the time, you hurt, are stinky, getting rained on or burning in the blazing hot sun, and constantly being dined on by various types of bugs – on the neck, on the hands, on the cheeks and of course, on the forehead. Now think about eating meals after sampling soils and the appeal of eating with fingers and nails all ringed in black.

Think about identifying plants in the dark cozy confines of the tent that you share with your coworker because, let’s face it, it takes a special woman to carry both a full sized shovel and her own tent into the backcountry.

This is me eating dinner sans utensils. I’m happy that the pot hadn’t gotten knocked over that night, that I was eating, and that it wasn’t “twig surprise”.

So now that we’d driven, sampled, and camped, picture leaving: packing up, packing out and throwing our wet gear into the back of a closet on wheels, squeezing into that disaster area, and heading out. By this time, I’m annoyed at Kat, she is thinking about murder, and the toilet paper is lost somewhere in the jumble. When we stop in small towns along the way, wide-eyed children back away from us and adults rummage in their pockets for change. Great! Halfway done! Just a few more sites and then we’d head home to a break that was never long enough.

Then Repeat

The break would include laundry, shopping, data drop-off, showering, relaxing, not camping. It would include remembering the previous weeks, the grimacing and sweating, our skin discoloring for one reason or another. Could we, would we, do it all again the next week?