Why do bats use buildings and other anthropogenic structures? A study of big brown bats from 2001-2005 in Fort Collins, Colorado found that bats select roost sites in anthropogenic structures (those made by people) that are warmer than randomly sampled buildings (Neubaum et al. 2006). So why does this matter if you are a bat? In summer, most large groups of bats using these structures are composed of adult females who use these sites we refer to as maternity colonies to give birth to their pups. The mother bats raise their pups for the first couple of months of their life in these safe locations. Soon after giving birth, mom resumes nightly drinking and foraging trips for insects. In the first several days after the pup is born, the mother bat may return multiple times per night to check on and nurse her pup at the roost. As temperatures outside drop each night, those inside the roost (i.e. building) remain warm, effectively providing an incubator for the pup while mom is gone. The frequency of mom’s nightly comings and goings slow as the pup grows older. A cool study by Lausen and Barclay (2006) showed that female bats gave birth earlier and pups matured faster when they roosted in buildings that were warmer than rock crevices. Consequently, a warmer roost means pups will mature more quickly and may have a better chance of surviving their first winter and year of life.

groups of bats using these structures are composed of adult females who use these sites we refer to as maternity colonies to give birth to their pups. The mother bats raise their pups for the first couple of months of their life in these safe locations. Soon after giving birth, mom resumes nightly drinking and foraging trips for insects. In the first several days after the pup is born, the mother bat may return multiple times per night to check on and nurse her pup at the roost. As temperatures outside drop each night, those inside the roost (i.e. building) remain warm, effectively providing an incubator for the pup while mom is gone. The frequency of mom’s nightly comings and goings slow as the pup grows older. A cool study by Lausen and Barclay (2006) showed that female bats gave birth earlier and pups matured faster when they roosted in buildings that were warmer than rock crevices. Consequently, a warmer roost means pups will mature more quickly and may have a better chance of surviving their first winter and year of life.

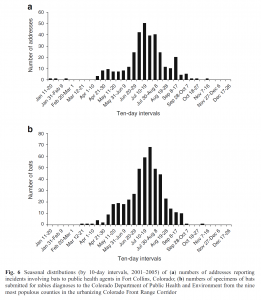

Eventually, the pups begin training to fly and learn to hunt insects. During this time window, usually from mid-July to early August, a spike in bat encounters is reported to health departments (See Graph of cases in "What diseases are associated with bats"). This spike in reports can be attributed to inexperienced young who crash land or exit/enter the roost at the “incorrect” locations, often leading to bats in living spaces (O’Shea et al. 2011). Roosts in buildings also allow bats to utilize areas in close proximity to additional food resources such as agricultural fields that may be situated adjacent to

developed areas. Bats remove these agricultural pests, which provides a beneficial service to us by reducing the use of pesticides!

What diseases are associated with bats?

Rabies: Research looking at the prevalence of rabies in an urban population of bats in Colorado suggests that many individuals have antibodies to the disease, indicating that they have been exposed to the virus but did not die (O’Shea et al. 2014). The amount of rabies antibodies, or seroprevalence, was lowest when bats were stressed, such as in a drought year. Relatively few bats become sick from rabies, < 0.5% of individuals in a large colony of Mexican free-tail bats, and only 10% of bats turned in for testing being rabies positive (Constantine 2009). Sick bats generally exhibit the paralytic form of the disease where individuals act lethargic versus the aggressive form, which is rare (Constantine 2009). As mentioned above, many bats submitted for testing are juveniles (Figure 1; O’Shea et al. 2011) who “took a wrong turn on their way out of the roost”. However, in the rare event that the rabies virus presents itself in any mammal, it is nearly always fatal. Consequently, it is important to note that anyone, or their pet, who has come into contact with a bat (touched a bat without protective gear) should contact their physician or local county health department immediately (Find your local public health agency). These professionals can guide you through the correct steps of action. If you know that contact did not occur, you do not have to worry about exposure.

Figure 1. (a) Proportions of big brown bats by age captured during summer and (b) numbers of bats submitted for rabies diagnosis to the Colorado Department of Public Health from the nine most populous counties in the urbanizing Colorado Front Range Corridor. Figure adapted from O’Shea et al. 2011 Journal of Urban Ecosystems 14:665-697.

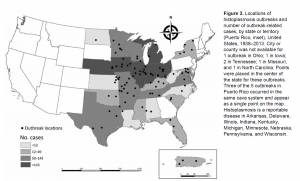

Histoplasmosis: A disease associated with, but not contracted by, large groups of bats using buildings is histoplasmosis. The human disease is caused by inhaling fungal spores that grow in guano piles of birds and bats. This fungus tends to be found in soils of humid environments more typical of Eastern North America (see Figure 3 below).  Hystoplasmosis outbreaks have not been documented in Colorado and even in areas where the fungus is prevalent, few people exposed to it (< 1%) develop symptoms (Benedict and Mody 2016). Despite low levels of the fungus in soils of Western states, those removing large guano piles should exercise caution. Minimize aerosolized dust by using water sprays or other dust suppression techniques and wear personalized protective equipment such as respirators when doing such work (Lenhart et al. 2004).

Hystoplasmosis outbreaks have not been documented in Colorado and even in areas where the fungus is prevalent, few people exposed to it (< 1%) develop symptoms (Benedict and Mody 2016). Despite low levels of the fungus in soils of Western states, those removing large guano piles should exercise caution. Minimize aerosolized dust by using water sprays or other dust suppression techniques and wear personalized protective equipment such as respirators when doing such work (Lenhart et al. 2004).

- For more information on these topics see the CDC website https://www.cdc.gov/rabies/index.html & https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2005-109/pdfs/2005-109.pdf

Coronaviruses’ like COVID-19: Although SARS-CoV-2, the virus that leads to the COVID-19 disease in humans, potentially spilled over from an Asian bat species, NO bat species in North America are known to carry the virus. Wildlife disease experts are concerned about humans exposing bats and several other mammals in North America to the virus, potentially making its management more difficult. Work with this new virus is ongoing with information changing rapidly as studies evolve. The big brown and Mexican free-tailed bats were challenged with COVID-19 in lab trials and showed no signs of infection (Hall et al. 2020; pers comm. Bosco-Lauth). The CBWG will update this section as new information becomes available. The take home for now is that Colorado bats do not appear susceptible to the virus.

Challenges of having bats in structures

Bats using anthropogenic structures, both inhabited and uninhabited, may present a number of challenges (Williams and Brittingham 2006).

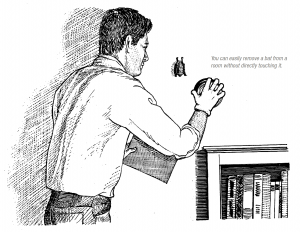

- Bat encounters in the living space: Adult bats, both those that are healthy or sick, and naïve juvenile bats may occasionally get into living spaces causing stress to human inhabitants. These scenarios are exacerbated when exit points are blocked without use of proper exclusion techniques, leaving bats little choice but to look for alternative exits that may include openings into living spaces. If one or a couple of bats gets into a living space, the bats will often leave if the lights are turned out and a door or window is left open. If this approach does not work, the occupant can carefully capture the bat by placing an empty coffee can or small box over the bat, gently sliding a piece of paperboard underneath the container, and releasing the bat outside in a safe location away from children and pets.

Figure from Williams, L. M., and M. C. Brittingham. 2006. A homeowner’s guide to Northeastern bats and bat problems. Penn State, College of Agricultural Sciences, Agricultural Research and Cooperative Extension.

- Guano accumulations: Guano piles and urine crystalization that have accumulated over a long time or from a large colony can cause odor and soil building materials.

- Parasites: In some cases, large bat colonies may be accompanied by the presence of invertebrate parasites. These parasites are specific to bats and generally leave humans alone. However, when bats are excluded from roosts, parasites may become apparent as they venture into living spaces to search of the missing bats.

Images of bat bugs (Cimex pilosellus) sometimes found with bats using anthropogenic structures. This bat parasite is similar in appearance to bed bugs, a parasite of humans, but not the same species. Microscope photo by R. Pearce.

- In other settings, bats may present challenges for health codes, such as in restaurants where droppings are not desirable or to renovations of structures (e.g., bridge renovation; Keely and Tuttle 1999) or daycare centers with toddlers not old enough to know not to touch bats.

Considerations for excluding bats humanely

A number of Best Management Practice’s for homeowners, nuisance operators, and agency staff should be taken into account when considering the exclusion of bats from any anthropogenic structure. Consider using a wildlife control operator that is certified to do bat exclusions (see NWCOA, https://www.nwcoa.com/page-18088 ). To help bats being excluded, ask your wildlife control operator if they follow guidelines recommended in the White-nose Syndrome National Plan as these best practices help prevent the spread of a fungus that kills bats while they sleep in winter hibernation. https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/mmedia-education/bats-in-buildings

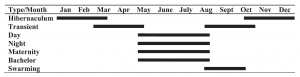

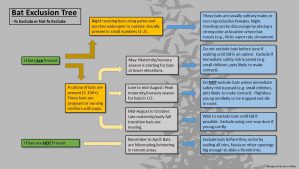

- Timing considerations are critical when considering exclusion of bats. Ideally, exclusion work should take place during times of year when bats are not present. For timing recommendations of when to conduct exclusions, see the Bat Exclusion Tree diagram below. Important factors to consider include:

- Can the work wait until the maternity colony has dispersed in autumn?

- Are there any risks of exposure to children, elderly with a compromised memory, or pets by waiting to exclude bats? If not, wait.

- Avoid the bat birthing window (June – mid August) if possible.

Seasonality of different roost type uses by Colorado bats. Figure from Neubaum, D. J., K. W. Navo, and J. L. Siemers. 2017. Guidelines for defining biologically important bat roosts: a case study from Colorado. Journal of Fish & Wildlife Management 8:272-282.

The following note in a side bubble provides why we make these recommendations based on what we know about use of buildings in Colorado by bats. “ BUBBLE: Based on work conducted in Colorado where buildings with known summer bat use were searched in winter (Neubaum et al. 2007), we believe that bats do not hibernate in buildings to any notable extent in Colorado. Work using radio telemetry and internal surveys have documented bats using caves, mines, and rock crevices during winter in the state (Neubaum et al. 2006, Armstrong et al. 2011, Siemers and Neubaum 2013, Neubaum 2018). While bats have been documented using buildings in the Midwest, it is our belief that this use is driven by resource availability (i.e., a lack of suitable natural roosting resources in that area). Colorado has many winter roosting options for bats with the possible exception of the Eastern Plains.”

- Roost sites situated internally

- When exclusion of bats is necessary, observe the structure at sunset to determine all exit locations used by the bats. Target these areas for use of one-way doors if bats are still present.

- It is important to run one-way doors for several days (5-10 days) prior to sealing shut the structure. If weather conditions are stormy during nights that the one-way door is installed, bats may stay inside so keep the device in place for additional nights to ensure all bats have left.

- Seal ALL openings that a thumb can fit into. Bats will switch to alternate entrances if the primary points are sealed shut. Bats do not chew on materials so insulation batting, foam used to cover pipes, and weather stripping can all work effectively to temporarily seal openings until permanent repairs are implemented.

Common locations used by bats to access roosting areas within buildings. Figure from Greenhall, A. M., and S. C. Frantz. 2004. Bats. in S. E. Hygnstrom, R. M. Timm, and G. E. Larson, editors. Prevention and control of wildlife damage.

- Use mesh made of small squares such as that found on window screens. Larger mesh, like those used for orchards, can tangle and entrap bats.

- Night roosts! Some bats use more open locations such as patio covers or entryway porches at night to digest food for a few hours before continuing on their nightly hunts for bugs. In these cases bats generally are not seen during daylight hours but often leave behind droppings. If exterior walls are composed of stucco or logs, these areas provide especially attractive surfaces for bats to hang on. Excluding bats from night roosts can be difficult but people have had success by placing a strong odor at the roosting location. For example, Vic’s vapor rub can be smeared on the wall or moth balls can be hung in a nylon. Smooth metal flashing can be installed as well which inhibits the bats ability to cling to the wall.

Building a bat box

Consider building a bat box to provide excluded bats with another option. Boxes that are mounted close to the original exit points previously used by the bats have a good chance of being discovered and used. In Colorado, boxes that have multiple compartments, painted a dark color, mounted high off the ground (10-15 ft), and facing eastern or southern aspects will provide more suitable roosting conditions for bats. Want to build a bat box? Check out some of these free patterns:

- A homeowners guide to Northeastern bats and bat problems https://extension.psu.edu/a-homeowners-guide-to-northeastern-bats-and-bat-problems

- Bat Conservation International’s https://www.batcon.org/about-bats/bat-houses/

- National Wildlife Federation https://www.nwf.org/garden-for-wildlife/cover/build-a-bat-house

- Buy a copy of The Bat House Builders Handbook by M. Tuttle & D. Hensley

Want to buy a bat box, there are many options:

- Bat Conservation & Management https://batmanagement.com/collections/homeowner-sized-bat-houses

Quick Contacts

-

- Colorado County Health Contacts: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/cdphe/find-your-local-public-health-agency

- Colorado Bat Experts: Regional representative that can help answer bat questions.

- Northeast – Paul Cryan, USGS (cryanp@usgs.gov)

- Denver Metro – Tina Jackson, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (tina.jackson@state.co.us)

- Southeast – April Estep, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (april.estep@state.co.us)

- West Slope – Dan Neubaum, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (daniel.neubaum@state.co.us)

Literature referenced in developing these recommendations.

Benedict, K., and R. K. Mody. 2016. Epidemiology of histoplasmosis outbreaks, United States, 1938-2013. Emerging Infectious Diseases 22:370-378. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26890817/.

Constantine, D. G. 2009. Bat rabies and other lyssavirus infections: Reston, Va., U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1329, 68 p. Available at: https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/cir1329.

Greenhall, A. M., and S. C. Frantz. 2004. Bats. in S. E. Hygnstrom, R. M. Timm, and G. E. Larson, editors. Prevention and control of wildlife damage. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdmhandbook/46/?utm_source=digitalcommons.unl.edu%2Ficwdmhandbook%2F46&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages.

Hall, J. S., S. Knowles, S. W. Nashold, H. S. Ip, A. E. Leon, T. Rocke, S. Keller, M. Carossino, U. Balasuriya, and E. Hofmeister. 2020. Experimental challenge of a North American bat species, big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus), with SARS-CoV-2. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases:1-10.

Keeley, B. W., and M. D. Tuttle. 1999. Bats in American bridges. Bat Conservation International. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237268659_Bats_in_American_bridges.

Lausen, C. L., and M. R. B. Robert. 2006. Benefits of Living in a Building: Big Brown Bats (Eptesicus fuscus) in Rocks versus Buildings. Journal of Mammalogy 87:362-370. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/BENEFITS-OF-LIVING-IN-A-BUILDING%3A-BIG-BROWN-BATS-IN-Lausen-Barclay/039cf9c3cf346c8a3eeb65b77a115dd7cc839e3f.

Lenhart, S. W., C. M. P. Schafer, M. Singal, and R. A. Hajjeh. 2004. NIOSH: Histoplasmosis: Protecting Workers at Risk - Revised Edition. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Cincinnati, Ohio. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2005-109/pdfs/2005-109.pdf.

Neubaum, D. J. 2018. Unsuspected retreats: autumn transitional roosts and presumed winter hibernacula of little brown myotis in Colorado. Journal of Mammalogy 99:1294-1306. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/99/6/1294/5120206.

Neubaum, D. J., K. W. Navo, and J. L. Siemers. 2017. Guidelines for defining biologically important bat roosts: a case study from Colorado. Journal of Fish & Wildlife Management 8:272-282. Available at: https://meridian.allenpress.com/jfwm/article/8/1/272/204241/Guidelines-for-Defining-Biologically-Important-Bat.

Neubaum, D. J., T. J. O'Shea, and K. R. Wilson. 2006. Autumn migration and selection of rock crevices as hibernacula by big brown bats in Colorado. Journal of Mammalogy 87:470-479. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/87/3/470/896483.

Neubaum, D. J., K. R. Wilson, and T. J. O'Shea. 2007. Urban maternity-roost selection by big brown bats in Colorado. Journal of Wildlife Management 71:728-736. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229683317_Urban_Maternity-Roost_Selection_by_Big_Brown_Bats_in_Colorado.

O'Shea, T. J., D. J. Neubaum, M. A. Neubaum, P. M. Cryan, L. E. Ellison, T. R. Stanley, C. E. Rupprecht, W. J. Pape, and R. A. Bowen. 2011. Bat ecology and public health surveillance for rabies in an urbanizing region of Colorado. Urban Ecosystems 14:665-697. Available at:

O'Shea, T. J., R. A. Bowen, T. R. Stanley, V. Shankar, and C. E. Rupprecht. 2014. Variability in Seroprevalence of Rabies Virus Neutralizing Antibodies and Associated Factors in a Colorado Population of Big Brown Bats (Eptesicus fuscus). PLoS ONE 9:e86261. Available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0086261.

Siemers, J. L., and D. J. Neubaum. 2013. White River National Forest Cave Bat Survey and Monitoring – 2013. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University and Colorado Parks and Wildlife. Available at: https://cnhp.colostate.edu/download/documents/2013/2013_WRNF_Cave_Report.pdf.

Williams, L. M., and M. C. Brittingham. 2006. A homeowner’s guide to Northeastern bats and bat problems. Penn State, College of Agricultural Sciences, Agricultural Research and Cooperative Extension. Available at: https://extension.psu.edu/a-homeowners-guide-to-northeastern-bats-and-bat-problems.